|

For immediate release

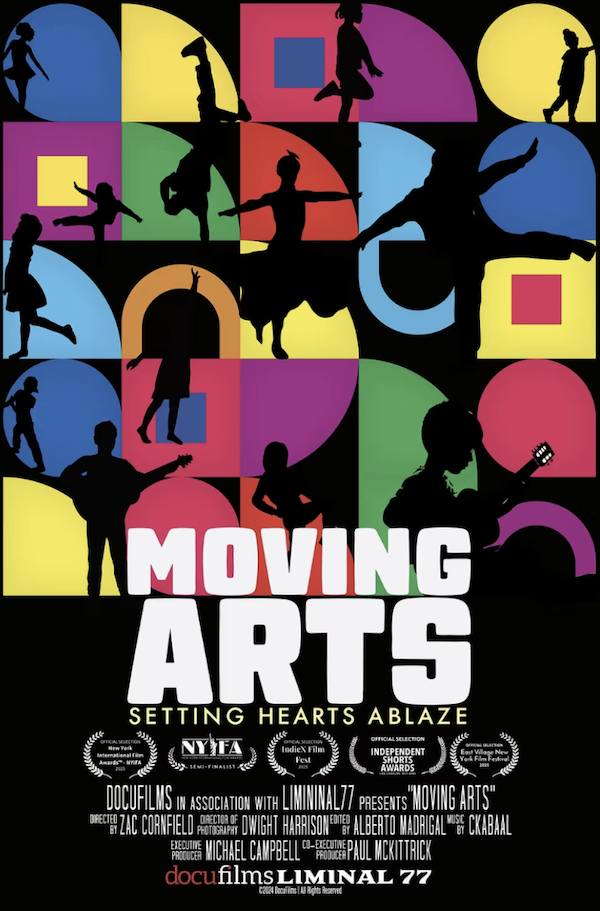

Moving Arts Documentary Moving Arts | Setting Hearts Ablaze Nominated for 2025 Rocky Mountain Southwest Emmy ESPANOLA, NM — Moving Arts Española is proud to announce that its documentary, Moving Arts | Setting Hearts Ablaze, has been nominated for a 2025 Rocky Mountain Southwest Emmy Award. This recognition honors the powerful storytelling and impact of Moving Arts’ mission touplift Northern New Mexico youth and families through arts, culture, and community. Produced in collaboration with Docufilms, Moving Arts | Setting Hearts Ablaze captures the heart of the organization’s journey, its students’ creativity, and the transformative role of the arts in the Española Valley. The nomination marks an exciting milestone for Moving Arts, reflecting not only the dedication of its team but also the resilience and spirit of the community it serves. “We are absolutely thrilled and deeply grateful for this incredible recognition,” said Salvador Ruiz, Chief Executive at Moving Arts. “Working with Docufilms gave us the opportunity to share our story in such a meaningful way. This nomination shines a light on the passion, perseverance, and artistry of our students and families.” The Rocky Mountain Southwest Emmy Awards, presented by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS), honor excellence in television and media across Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and parts of California. The winners will be announced at the 2025 Rocky Mountain Southwest Emmy Gala later this year. Moving Arts Española extends its heartfelt gratitude to Docufilms, its students, families, and community supporters for making this achievement possible. Additional accolades for the film include: ●Official Selection – Los Angeles Independent Shorts Awards ●Official Selection – East Village New York Film Festival ●Official Selection – IndieX Film Fest ●Best Original Score - TELLY Awards ●Best Documentary - TELLY Awards ●Best Social Impact - TELLY Awards About Moving Arts Española Founded in 2008, Moving Arts Española provides low-cost, high-quality arts education and wellness programs to the youth and families of the Española Valley. With a mission to nurture creativity, self-expression, and community resilience, Moving Arts serves more than 600 children and families annually through dance, music, theater, and visual arts programming. For press inquiries, film screenings, or interviews, please contact: Email: [email protected] Phone: 844-623-2787 Website: movingartsespanola.org Learn more about the film and upcoming screenings at movingartsespanola.org/events

0 Comments

Left: In a recent picture, Javier Martinez, commission president of the Distrito Community Ditch acequia, stands knee-deep in silt where the acequia once ran. Right: A dog runs along a nearby acequia that also was damaged. The acequias are among at least 36 in Northern New Mexico that suffered at least some damage in recent storms, according to the New Mexico Acequia Association. (Photos courtesy Mykel Diaz and Serfina Lombardi) Rainstorms last month in Northern New Mexico damaged several dozen acequias, many of them severely, according to an advocacy group concerned that without state or federal help, farmers who rely on the ancient irrigation canals will lose at least two growing seasons. At least 36 acequias in Taos, Rio Arriba and Santa Fe counties sustained damage in three storms last month, according to Vidal Gonzales, policy and planning director for the New Mexico Acequia Association. He told Source New Mexico on Tuesday evening that most of the damage came from two storms Aug. 25 and Aug. 29. All told, 19 acequias in the Chimayó area, along with six near Pojoaque and 11 others near Ojo Caliente, sustained several millions of dollars in damage in the powerful rainstorms, he said. The storms created floods that poured into the channels, generating enough pressure to crack metal headgates. Debris flows elsewhere left acequias full of silt that will have to be dug out before they can flow again, he said. Others may have to be rebuilt, he said. “Some of them got blown out just from such a high-intensity rain event in such a short amount of time,” Gonzales said, who shared pictures of the damage. Acequias leaders, known as mayordomos, have shared damage assessments with the Acequia Association in recent days, as the organization begins advocating for county or state disaster declarations that would unlock some funding, Gonzales said. The group hopes to compile all that information for Rio Arriba and Santa Fe county officials this week, he said. But even if Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham were to approve a state declaration, which would mean at least $750,000, Gonzales said he’s unsure where the rest of the money will come from. While a federal disaster declaration could provide needed individual assistance and help to public entities like acequas, “I don’t see that happening with this administration,” Gonzales said. Other federal agencies, like the Emergency Watershed Protection Program or the Natural Resources Conservation Service, are short-staffed and overwhelmed, he said, with other disaster projects and spending cuts. And state funds the Legislature passed specifically for acequias earlier this year have already been allocated, primarily to small projects or engineering and design. Gonzales attributes the severity of the floods to human-caused climate change, he said, along with longstanding watershed degradation that will require a multi-faceted approach to address. “We’re really between a rock and a hard place here in New Mexico with all these disasters and climate change and everything affecting us,” he said. The storms mark just the latest natural event to damage the historic irrigation canals, which are largely unique to New Mexico. The association earlier this year estimated that150 acequias were damaged due to recent wildfires, particularly due to post-fire flooding, in northern and southern New Mexico.

The Legislature in recent years has approved more than $100 million in disaster loans, including for specific acequias, to help them start recovering, but they often face bureaucratic challenges, including becoming designated public entities eligible for federal or state disaster assistance. Mykel Diaz, mayordomo of the Acequia de los Martinez Arriba near Chimayó, told Source that he’s already encountered some of those challenges for his acequia, because it runs over the boundary of Santa Fe and Rio Arriba counties. That’s making the damage assessment difficult, he said, along with other hurdles. He told Source that the flood damage has affected basically the entire Santa Cruz River Valley, including several major acequias. His acequia has slightly over 100 users — or parciantes — he said, and the Distrito Community Ditch nearby has about 200. Both suffered severe damage that will cost tens of thousands of dollars, at least, he said. The acequia Diaz oversees lost basically an entire mile-long stretch due to 20 “avalanches” that dumped into it during the Aug. 29 storm, he said. For acequias that have been in that area for several hundred years, seeing one storm wipe so much out demonstrates “the fragility of the system,” he said. “It just took one epic rainstorm that put two inches of rain in like an hour,” he said, “and took us out.” Diaz’s acequia has some money to at least begin digging out, he said, which is a rarity among acequias. But he’ll need to convince parciantes to approve moving $10,000 they recently approved for a new diversion project toward recovering from the disaster. “If we don’t re-allocate that money, then we’re not going to have any water to divert,” she said. “It’ll be a futile project.” For other required spending, Diaz said he just hopes that the acequia will somehow be reimbursed for the “freak of nature” storm. “Mother Nature really gave it to us that day,” he said. By Sara Wright Yesterday I briefly attended the well-advertised (thousands of people) Monarch Festival. Held at our local land trust my purpose was to watch a young neighbor participate in the final parade.

In the time I spent there I saw adult women dressed in butterfly wings and monarch shirts, both children and adults wearing butterfly antenna created out of pipe cleaners (bought at the festival), children with butterfly tattoos, stenciled monarch caterpillars on clothing. The list goes on. The merchants, and there were many, had a good day and the organization made lots of money. This a surely a children’s festival! It is also a delightful place to meet friends and to buy many products. There were so many creative projects for young people of all ages to engage in, and I so enjoyed seeing the paintings (thank you Rebecca) for your brilliant art-work. All the participants seemed delighted with the vendors wares. Most disturbing to me is that children are being inculcated into the belief that it’s just fine to tag butterflies and that the lives of these insects really don’t matter. All creatures in nature remain less than human, without feelings or sentience. The same old story continued for another generation. I volunteered for this land trust for four years and wrote 50 articles for them during the same period but have made the decision to stop participating because of monarch tagging. This practice extends well into September. Tagging is lauded as a success story. Why am I so upset? First of all, because these beautiful creatures are treated like a less than human thing. Worse, these folks tag the very monarchs that make the arduous trip to the Mountains of Mexico to spend the winter. The ones with these tags are often found dead in Mexico where people are hired to find them. These butterflies are unable to finish their journey north to lay eggs in the spring, the only monarchs who live nine months, and their circle of life has broken. Virtually everyone must know by now that these butterflies are in steep decline. Western science continues to research the effects of tagging on how the paper tags attached to the hind wing of a butterfly effect the actual life of a monarch. Good field research takes years but there is enough scientific evidence out there to suggest that these butterflies’ lives are being threatened by this practice. Of course, pesticides may also be a culprit because virtually everyone uses them. Add habitat loss etc. and the reader can draw his or her own conclusions. Because I have discussed the effects of tagging elsewhere on this blog (and through many publications throughout the country) I will not repeat what I learned, except to add that incoming research is indicating that tagging poses more threats than originally believed to the monarch butterfly. Unfortunately, only researchers like I am, are willing to dive into more scholarly articles to find out what is really happening. Although the land trust is bulging with an overly stuffed garden of flowering plants, I saw only one monarch land on a Mexican sunflower as we were leaving. I stopped to take a picture amazed that the butterfly stayed so long perched on this one blossom. It wasn’t until I looked at my photos that I understood why. This monarch was wearing a tag, and was no doubt recovering from the trauma of being caught etc. A fitting end to my story. Sept. 27 is a fee free day on national forests and grasslands

Release Date: September 16th, 2025 Contact Information: Claudia Brookshire 505-438-5320 [email protected] On September 27, the Santa Fe National Forest is participating in a variety of events in honor of National Public Lands Day – the nation's largest single-day volunteer event for public lands. Join us for the following events: National Public Lands Day at Bandelier National Monument

Pecos to Pecos Road and River Cleanup

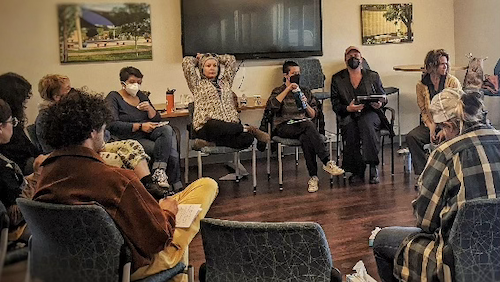

To learn about other events, visit the National Public Lands Day event locator. There are a variety of opportunities for volunteers to pitch in on improvement projects in their communities. National Fee-Free Day National Public Lands Day is also designated as a Fee-Free Day. On these special fee-free days, standard amenity fees are waived for day use sites — like picnic areas, developed trailheads, and destination visitor centers. Some exceptions apply. About 95% of national forest land can be enjoyed fee-free, year-round. Where fees are assessed, at least 80% of these funds are reinvested at the collection site, to provide needed maintenance and services or pay for future improvements. For more information about interagency passes, visit the Forest Service’s Passes and Permits page. The remaining fee-free observance for 2025 is Veterans Day on Nov. 11. Before you go to the Santa Fe National Forest, visit the forest website for information on recreation opportunities and any public safety alerts. If you want to make reservations for these and other federal lands, visit Recreation.gov. About the Forest Service: The USDA Forest Service has for more than 100 years brought people and communities together to answer the call of conservation. Grounded in world-class science and technology– and rooted in communities–the Forest Service connects people to nature and to each other. The Forest Service cares for shared natural resources in ways that promote lasting economic, ecological, and social vitality. The agency manages 193 million acres of public land, provides assistance to state and private landowners, maintains the largest wildland fire and forestry research organizations in the world. The Forest Service also has either a direct or indirect role in stewardship of about 900 million forested acres within the U.S., of which over 130 million acres are urban forests where most Americans live. By Karima Alavi All photos, compliments of Aimee Wilson This November, for the first time, Dar al Islam will be the site of a grief retreat, “Becoming Sanktuaree” co-hosted by unashay and TEN (The Emergence Network.) Unashay offers land and community-based presence, sanctuary, and creative arts for those who are grieving. Abiquiu’s own Aimee Wilson is the founding Executive Director of this organization that helps people take time to court, rather than “fix” what hurts. With gatherings in Abiquiu and other New Mexico sites such as Albuquerque and Santa Fe, the intention is to recognize and honor the Rio Abaja Rio, or River Beneath the River. According to the unashay website, the River Beneath the River is a “vibrancy running from below which, when not tended, begins to erode and turn into a thousand different arrows upon itself and the ‘other’: and when tended, flowers into a thousand different petals.” Aimee Wilson and the Early Seeds of Unashay Before moving to Abiquiu, Aimee Wilson (who uses the pronoun They) worked as a social worker in Philadelphia, helping women as they transitioned from being unhoused to finding a home. They’ve also turned to music and art as a means to reach out to people. They moved to Abiquiu in the autumn of 2017. When they first came to Abiquiu, they had lost their mother very suddenly. Within that same year, Aimee also lost their best friend. With the loss of the two people most important to them, Aimee says they felt isolated and became “a shell of a being,” even among the comforting beauty of the surrounding land. Dealing with their own grief at that time, the idea of unashay came from the visceral experience of longing, and the need to understand what other people do when they go through loss. That’s what led them to enter the work of grief counseling. Another element of Aimee’s work is a series of Noria Grief Cafes. These small gatherings that take place around New Mexico are named for the Arabic word for Water Wheel, referencing the way something can reach deep within river water and pull up something that was stuck until there’s a great release. More information on these free gatherings can be found here: https://unashayhome.com/noria-cafe What is the purpose of the Sanktuaree Program to be held in Abiquiu? With many people feeling embedded in a socio-cultural-political climate that encourages us to pursue hyper-individuality and control, we’re endlessly distracted from making contact with wounds that lie beneath the messages of modernity. The purpose of Becoming Sanktuaree is to inhabit the sanctuaries we dearly long for by offering experiential community-held spaces of inquiry, presence, encounter and creation while acknowledging stories of those who feel taken by grief. Attendees will participate in sharing dialogue, listening deeply, being present, and building relationships. The hope is to embolden participants to enter into a lived experience of sanctuary in their own bodies, homes, and communities—something that includes community with our other-than-human kin, such as the four wolf-hybrids that live in Abiquiu with Aimee Wilson, and help “host” people visiting the site. And what is meant by “Sanctuary”? Aimee and the other host, Aerin Dunford, imagine it as places (within us, and outside us) where we welcome the experience of sitting with, and touching our shared pain and beauty. Who is this program for? For grief-workers, death doulas, care givers, artists, people concerned about the ways we are living in these strange end-times, spiritual seekers, disillusioned activists and those wanting to connect, despite wounds around connection. It’s for those who want to put into practice what is learned and co-created in this space. People willing to turn toward their pain. It’s for parents, educators, therapists, and those who simply feel isolated and are grieving in these times. Logistics of the upcoming session: The session is actually a hybrid program with Thursday Zoom-only sessions on October 2, 16 and 30, leading toward a final hybrid Zoom and in-person event that coincides with the arrival of onsite participants at Dar al Islam. Participants can select an entirely online experience, or they can join others for the in-person gathering in Abiquiu. On-site participants will arrive in the early afternoon of Thursday, November 13, and depart on the morning of Sunday, November 16. Seated atop a rural mesa in Abiquiu, New Mexico, where the high desert meets riparian woodlands, Dar al Islam is a non-profit education and retreat facility. For further information on Dar al Islam, you can read the article, “Out of the Earth of America; The Built Environment and Communal Ethics of Abiquiu’s Dar al Islam” by board members Dr. Fatima van Hattum (who grew up in Abiquiu), and Dr. Asma Sayeed. Click here to access that article: https://themaydan.com/2023/05/out-of-the-earth-of-america-the-built-environment-and-communal-ethics-of-abiquius-dar-al-islam/ Please note: The registration deadline for Becoming Sanktuaree is next week: THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25 How to register for the Becoming Sanktuaree retreat: There are different pricing scales for those who sign up only for on-line participation and those who wish to add a stay at Dar al Islam at the end of the four zoom meetings. You can find detailed information on fees and the sliding scale at this website: https://form.typeform.com/to/fl4a6iGf When I spoke to Aimee last week, they noted that there were already 40 people registered for the full program, including the gathering in Abiquiu, and 174 registrations for the four online Zoom gatherings. People will be joining from all over the world. In fact, on the day of our interview, the newest guest had registered from Zimbabwe. Special Program on Saturday, November 15, 2:00 -10:00 pm. OPEN to the PUBLIC: The biggest challenge Aimee and others face in their attempt to reach out to those in need is funding. A core group of 12 volunteers, or “companions” is involved in expanding unashay work to include bringing services, or even something as simple as a friendly visit, to people in need of both emotional and physical assistance. Unashay recently partnered with Gerard’s House in Santa Fe, a safe place that offers support and crisis response to children, teens, parents, and adult caregivers, including seven weekly grief support groups in both English and Spanish. Unashay also plans to do on-call home visits, but they need funding for training retreats. With financial support being withdrawn from many organizations that provide much-needed services, unashay is reaching out to people who would like to assist and support their work. For this reason, the weekend program will take time on Saturday, November 15 to offer a series of events that are opened to the public. Funds from ticket sales for the five-course meal will be divided between unashay and another organization called the Earthseed Black Arts Alliance. This nonprofit organization is led by Nikesha Breeze, a multidisciplinary artist living in Taos, and supports black youth through arts outreach. How you can help, while enjoying a day of inspiration: Special program on November 15 On Saturday, November 15, Unashay Grief Sanctuary will host a day at the stunning adobe vaulted complex of Dar al Islam in Abiquiu, New Mexico to fundraise for its land-based sanctuary and core programs for the underserved grieving of Northern New Mexico, and beyond. Beloved friends, partners, council, neighbors, artists and more will convene at the mosque to connect, listen, walk the land, raise support, create, and experience sanctuary. In a time where loneliness has become an epidemic, and unmet grief resides below and between so much of the world's preventable suffering, we long to inhabit sanctuary in its myriad of forms. This day is an invitation to do just that. It is not designed to be a '1-off event', to proclaim a message, and later resume our lives. It is, rather, meant to quicken a memory--that we are already such sanctuaries, in the miraculous hem of our everyday lives, and examine how we can continue living into such beingness, if we choose. The day will include a number of ways to participate. Guests are welcome to attend any one part, or the entire day. See the day's outline below, and explore the different ticket options on the unashay events page at https://opencollective.com/unashay-sanctuary/events/grief-feast-sanktuaree-fundraiser-edcfffd3 2 to 6pm⎯ Sanktuaree Bazaar + Dr. Bayo Akomolafe, followed by Community Discourse. Attend the “Sanktuaree Bazaar” (which will be a bazaar of experiential spaces) from 2 to 6pm⎯ to roam the stunning vaulted complex of Dar al Islam, and experience the different forms of sanctuary our trans-local participants collaboratively build and share. Dr. Bayo Akomolafe will share a public talk and end with an open community discourse, among elders and community members.

Participants from our former two-month Becoming Sanktuaree experience will have co-created physical experiences of sanctuary throughout the hallways and rooms of Dar al Islam. Guests are welcome to walk these hallways, experiencing the sanctuaries-within-the-sanctuary, joining us for this pre-feast of the soul.... before we partake in a physical feast. Note: Due to recent issues with travel to the U.S. from overseas, Dr. Akomolafe will be joining by Zoom, rather than in person. 6p to 8pm⎯ Grief Feast with Nikesha Breeze This ritual dinner will be co-hosted by Earthseed Black Arts Alliance and unashay. It will be a slow five-course meal, with powerful Taos artist Nikesha Breeze to court us through each part of the meal representing different layers of grief. Proceeds from this portion of the night will be split between Earthseed and unashay. The delicious dinner will be presented by Kohinoor, a catering company owned by Rehana Archuletta, one of several children who grew up on the Dar al Islam property. 8 to 10pm⎯ Music Performance with Luz Elena Mendoza (of Y L Bamba) Old friend Luz Elena Mendoza will perform an intimate solo set to close out the day. Between Luz's siren voice and the stunning vaulted ceilings of Dar al Islam, this is not a night to be missed. ** Guests who travel to attend this day are welcome to book affordable dormitory-style accommodation at Dar al Islam on 11/15, for an additional fee (until we sell out!). Or, find alternative housing at nearby Abiquiu Inn, Ojo Caliente Hot Mineral Springs, Ghost Ranch, local Airbnbs, camping sites, etc. Recommended to book asap! ** Proceeds from the Sanktuaree Bazaar, Bayo Akomolafe's community discourse, and Luz Mendoza's performance will support Únashay Grief Sanctuary’s development and community services for the underserved grieving. Proceeds from the Grief Feast will support both Earthseed Black Arts Alliance and unashay. Tickets for separate SATURDAY events, or for the full day, are available at: https://opencollective.com/unashay-sanctuary/events/grief-feast-sanktuaree-fundraiser-edcfffd3 Important registration information: Because the caterer needs a headcount for the Grief Feast on Saturday November 15, the registration deadline for the FIVE-COURSE MEAL is SUNDAY, NOV. 9 You can register for all other November 15 activities up to the day of the event. By Felicia Fredd, Enchanted Garden Productions

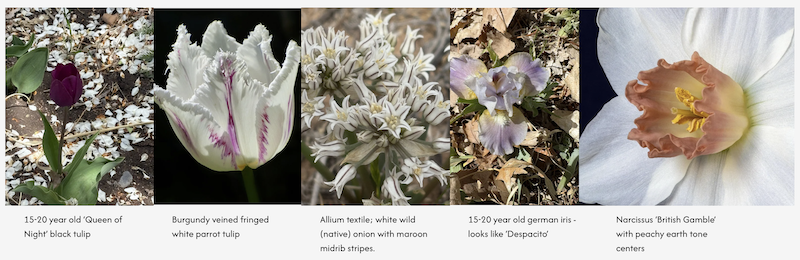

I’ve worked with a lot of people who relate to their gardens/landscape as a war zone . There are the battles with the weeds, the failing irrigation systems, the bugs, the rabbits, the gophers, the very soil. There are the intolerable leaves that fall so beautifully to the ground. The plant that isn’t quite as pretty as the one seen somewhere else—which is frustrating. The unpicked fruit that’s “not worth it anyway.” The allergens. The artless hacking that ensures ugliness and justifies replacement with something ‘nicer.’ Gawd. I am deeply sympathetic to the exasperation people experience with gardens. They tell me about it. I’m there to help fix things, but I’ve learned that even when people ask questions, explaining things about plants, or bugs, or soil itself scarcely penetrates. Most of the time we are simply trying to bring garden spaces into line with a vision or concept from something seen elsewhere - not actually trying to learn horticultural science. We hope to get along with general ideas about how things are done, and accept the problems that may go with it. Social mirroring isn’t ‘bad’. I’ve often noticed that the nicest feeling neighborhoods feel good because there is a certain design continuity that merges into one cohesive PLACE. It promises to simplify life, and yet it’s likely not altogether true, and definitely not here in the high desert where there is such a mismatch between aesthetic norms and environmental reality. I’m on a mission to get away from all the wasteful grind and frenzy, and I believe it begins with seeing the unique opportunities and aesthetics of our own particular sites. Native plants are a big part of that, but even more broadly, I think it really helps to shift one’s attention from what’s not working (and maybe letting those things go) towards what is actually working. That’s my big tip. I am trying to make a point out of calling out beautiful or interesting things while in the garden with people. Just that - noticing stuff that’s working. Not only does it help build morale, it slowly opens the door to more interesting and environmentally compatible possibilities. It doesn’t have to be about native plants. I personally love it when it is, but one way or another, you’re nudging toward less cyclical destruction and waste. Like hey, that native four-wing saltbush (what the bleep is that?) is really beautiful in the fall with all those weird chartreuse seed bracts. Can we do something with that? Time it with something that would accentuate that? As a small example, I’m working on a spring bulb order (in my life, fall means planning for spring; that’s another tip) and I’m making selections based on something I saw last spring in & for the same garden that I love. What I saw was the early crabapple blossom drop spread out across old tulip and daffodil beds. Evidently, my visits hadn’t ever coincided with that event. It was just gorgeous, but perhaps it was more the pumped up version that played out in my head. At the same time in another nearby area, I noticed the sweetest little relic dwarf iris emerging from a bed strewn with dried hawthorn leaves. The subtle textures and colors of all have become inspiration for a planned reboot on that spring garden anchored on two core species that have survived for 15-20 years after initial planting. That’s a pretty good survival rate around here. The following is an image strip to illustrate existing and proposed garden additions: Who's scruffy looking? By Zach Hively I never planned on sprouting a beard. In fact, for many years there, I went entirely beardless. Then I hit puberty. I continued to go beardless for several presidential administrations thereafter, but not for lack of trying. Frankly, the best beard I grew between middle school and middle age* was the first one. An adult suggested I might try using the electric razor I had received for Christmas. The reason for my razor was not apparent to me until I locked myself in the bathroom and got close—real close—with the mirror. There! And there! Actual hairs growing straight out of my neck! I lopped them off and felt, maybe for the last time, like a real man. A man who had to shave. A man who did not yet realize how awful is the burden of shaving, but a man nonetheless. Oh, I tried to equal that first beard from time to time. I sported chin bristles and minimalist sideburns for a little while in high school, but still I had to shave everything in between on the reg, as if with purpose, lest anyone realize that no actual hairs grew anywhere in between. Otherwise, I went clean. Going clean meant calculating the upper limit of how many days I could avoid shaving my mug before that weird blank patch on my cheek became unavoidably apparent. Then I’d stall for another week before shaving. Until one fine month in 2013 when I just … didn’t. I remember it well. It was September, and the delicious scent of pumpkin spice was just hitting the air, which was still a novel marker of time’s progression. (This was back before autumn merchandising kicked off in earnest on Boxing Day for the entire year to come.) An acquaintance, or perhaps it was my girlfriend, commented on my beard. My beard? I scrambled to the bathroom mirror like I was oblivious and thirteen all over again. Only I didn’t have to look so close this time. My face was, in fact, furry. And if I may say so—which I may—this incidental beard improved my face, primarily by hiding it. Beards have come into fashion since then, and fallen back out, and probably come back in again. I couldn’t tell you where beards stand now, or what styles are preferred by the five or six men whose opinions are worth anything.

I just know mine is not going anywhere. Its length will always land between “clearly on purpose” and “saving up for my first Harley.” I will trim it as seldom as possible while still ensuring it can’t wind up in my own mouth in my sleep. And I will use it—never on purpose, but it happens—to make friends. Guy friends, that is. We guy-like individuals are not notoriously capable of bonding over much more than, I don’t know, mustards? Whereas I have witnessed lifelong friendships form between non-guy-like individuals over—and I am serious here—laundry detergent. Laundry detergent is clearly far too substantive for us guy-like folks. But. If you want the delight and wonder of hearing guy-adjacent people discuss essential oils and preferred fragrances, bring up beards. (Note: This outcome is more likely if everyone involved, no matter how much we don’t talk about it, has a preferred laundry detergent.) Because yes: Even if it took a dozen years, this beard of mine is no longer just my least inconvenient headshot accessory. It is a style choice, and part of my physical being. I will write down other guy-like people’s advice on shea butter and argan oil, whatever an argan is. I will promptly forget ever to lookat that advice, but I will know it exists. And I will remember to use my specialty beard brush at least once per pumpkin-spice season. It deserves my care and attention, my beard does. I’m grateful it finally came in, and that it has filled itself in by now. Even though it is turning salty, it still hides most of my zits. Which is really why it’s staying put. ‘Whenever there’s changes to SNAP, we see food lines grow.’ By PATRICK LOHMANN Courtesy of Source NM The line at a local food bank’s weekly distribution in Albuquerque’s International District has increased in the last few years, organizers say, as neighbors in nearby homes join the queue alongside the growing population of unhoused residents. Marissa Brown, who runs the Roadrunner Food Bank distribution, says the line has increased by approximately 50 households to 225 each week. She estimated a line once composed mostly of unhoused people pushing carts is now probably 60% people with roofs over their heads. “We are just seeing more of our neighbors who are housed coming, too, because it’s just hard for everyone,” Brown told Source New Mexico as people worked their way through the line Friday morning. “We’re really pleased that we can just expand that reach to anyone who might need it, but it certainly has expanded.” Even before cuts to the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program contained in the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” take effect, President Donald Trump’s second term has already hurt the food bank’s ability to feed hungry people in a state where more than one in five residents has food stamps, food bank officials told Source New Mexico on Friday. For example, inflation has reduced how much food Roadrunner can buy with donations or grant funding, and the federal “Department of Government Efficiency” cuts to emergency food assistance programs earlier this year by 30 truckloads of food worth a little more than $1 million, according to Roadrunner officials. On Friday, that reduced budget meant food recipients had less variety to choose from, she said, as they walked through the line at the International District Library, though the food bank did happen upon a donation of flower bouquets, giving recipients a “surprise gift of joy.” Still, Brown called it “frightening” to consider what will happen if the food bank has to rely solely on donations as people lose SNAP benefits, both at the distribution she runs and at food banks and other nonprofits across the state. “Even though the SNAP cuts haven’t quite happened yet, the [existing] benefits are not lasting as long,” she said. “So folks always do express how grateful they are that we’re here week after week, because they just wouldn’t be able to make it through the month.” Food banks across New Mexico have previously warned that they don’t have the capacity to feed all New Mexicans if SNAP goes away. Jason Riggs, Roadrunner Food Bank’s director of advocacy and public policy, told Source New Mexico in a phone interview Friday that the Albuquerque food line, which is growing and feeding an increasingly diverse group of people across the income spectrum, is a harbinger of the near future after SNAP cuts go into effect. “Whenever there’s changes to SNAP, we see food lines grow,” he said. New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee analysts told lawmakers at an interim legislative meeting Wednesday that one-in-four New Mexico children live in households without consistent or adequate food. Of the roughly 460,000 New Mexicans who receive SNAP benefits, more than 36,000 could lose them entirely due to their immigration status or new work requirements, according to the LFC analysts. The Legislature will convene Oct. 1 in a special session primarily to discuss how the state will adapt to the federal cuts. Riggs said he hopes the Legislature focuses immediately on how it will mitigate the impacts of SNAP’s new work requirements, which go into effect Jan. 1. “Within months, there’s thousands of people that are suddenly going to be subject to work requirements,” he said, and the state has to figure out how to explain what’s happening and identify resources as soon as possible. “All that has to happen extremely quickly in order for thousands not to just flat out lose SNAP. So regardless of where we point the finger for people losing SNAP, our concern at the food bank is people suddenly losing their food resource and relying more on our food pantries.” One of the people who could lose benefits is Kyle Neri, a military veteran who has lived on Albuquerque streets for the last few years with his dogs Mama and Bailey. He picked up a bag of mandarins and tins of beans and oatmeal Friday morning, along with a Ziploc bag of dog kibble.

He said a car crash a few years ago damaged his spine, but he was denied disability assistance. He’s making do with $120 a month in food stamps, he said, along with a veteran’s disability payment of $700 for his Army service in the late 1990s. But inflation is already making it nearly impossible, he said, to feed himself while trying to save for permanent housing. He said he’s “of course” worried about losing food stamps amid rising food costs. “You spend, like, $20, you get nothing now,” he said. “I’m trying to get me housing. Out here, it’s rough.” September 12, 2025 - Public Health - Awareness

SANTA FE – The New Mexico Department of Health is launching a region-wide “Are You Prepared?” campaign to encourage individuals and families to take simple steps toward readiness for emergencies. September is National Emergency Preparedness Month, during which public health officials across the northwest region will engage communities through outreach events, health fairs, and visits to public health offices, offering free resources linking directly to www.Ready.gov, the federal government’s all-hazards preparedness website. “Preparedness can seem overwhelming, but it all comes down to small actions that make a big difference,” said Mike Rose, Northwest Region Emergency Preparedness Specialist for the New Mexico Department of Health (NMDOH). “Knowing who will pick up your children if phone service is down, storing three days of water and creating a family meeting plan are all steps that can save lives and reduce stress during a crisis.” New Mexico communities face a range of risks including wildfires, floods, extreme heat, power outages, and public safety threats. Such events highlight the need for New Mexicans to have:

NMDOH’s Northwest Region public health offices can provide residents with an “Are You Prepared?” flyer of easy steps to take to prepare. The flyer includes a space for emergency contacts. The “Are You Prepared?” campaign goes hand-in-hand with the work of the New Mexico Medical Reserve Corps (NM MRC), which brings together trained medical and non-medical volunteers ready to support communities before, during, and after emergencies. Learn more about the NM MRC and sign up to volunteer. New Mexicans are encouraged to scan the QR code on campaign materials or visit www.Ready.gov to learn more about creating an emergency plan, creating a supply kit, and staying informed. Media Contact We would be happy to provide additional information about this press release. Simply contact David Barre at (505) 699-9237 (Office) with your questions. Versión en Español En un esfuerzo para hacer que nuestros comunicados de prensa sean más accesibles, también tenemos disponibles una versión en español. Por favor presione el enlace de abajo para acceder a la traducción. "¿Está Preparado?” campaña promueve la preparación para emergencias Under draft rule, 60% of the money must benefit rural communities By AUSTIN FISHER Courtesy of Source NM Local and tribal governments in New Mexico can expect to begin applying for state funding to support solar energy projects early next year, if not sooner, state officials told lawmakers on Wednesday.

At the New Mexico Finance Authority Oversight Committee’s meeting in Deming, NMFA Deputy Director Fernando Martinez said applications for the newly created Local Solar Access Fund will open in early 2026, but the agency is hoping to have them ready by December. The fund is a $20 million pot of public money for grants for solar energy and battery storage for tribal, rural and low-income schools, municipalities, counties, land grant communities and New Mexico’s seven regional Councils of Governments. The projects supported by the fund are meant to reduce energy costs for low-income households and community service providers; support the local renewable energy workforce; enhance community resilience during emergencies; and leverage other funding sources, according to Martinez’s presentation to the committee. The new law requires NMFA to provide project grants for designing and building solar systems, and help developers obtain state and local permits or apply for federal or other funding sources, the presentation states. “We’ll be in the meantime building the applications internally so that we have a really good system so that when we open it up, it’s a really straightforward process, and we have a really good client experience for them, so it’s not too difficult,” Martinez said. An advance copy of the proposed rule for funding decisions given to the committee on Wednesday also requires NMFA to work with the state Energy, Minerals, & Natural Resources Department to create minimum standards for proposed systems and metrics for applicants. Those metrics include capacity for the scope of work; project location; how much a project will contribute to a community’s “resilience;” and any other benefits that may result. The new law requires most of the funding to benefit rural communities. The proposed rule specifies at least 60% of the money, approximately $10.8 million, be allocated to rural communities with a total county population of 60,000 or fewer people. No more than 25% of the money can go to any one county, the rule states, including the county government itself. Half of New Mexico’s population lives in the 30 more rural counties, Rep. Kathleen Cates (D-Rio Rancho) told the committee, while the other half lives in Bernalillo, Santa Fe and Doña Ana counties. “We don’t want to forget about either 50% of the population,” Cates said. “I appreciate that the drafters of this bill understand that rural communities are at a disadvantage and are giving them more than 50% of the opportunity for this program.” The proposed rule sets a $16 million limit total for project grants and $2 million for technical assistance, leaving $2 million for NMFA to administer the program and cover any unexpected costs, NMFA spokesperson Lynn Taulbee told Source NM. New Mexico’s implementation of new solar funding law comes as the federal government reverses the prior administration’s moves to boost renewable energy production. A law signed by President Joe Biden in 2022 gave developers tax and energy production credits for wind and solar projects, but President Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” abruptly ended those credits in July. Then in August, the Trump administration clawed back $7 billion in grants for solar energy projects for low-income households from the same Biden-era law that would have benefitted 60 recipients, including EMNRD. New Mexico also has a different programfor businesses and low-income households to receive energy from solar farms. During the presentation, NMFA CEO Marquita Russel noted that both the NMFA and the legislative oversight committee will need to approve the Local Solar Access Fund’s rules by November. Once initially approved, the committee will have to sign off on any future changes, she said. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed