|

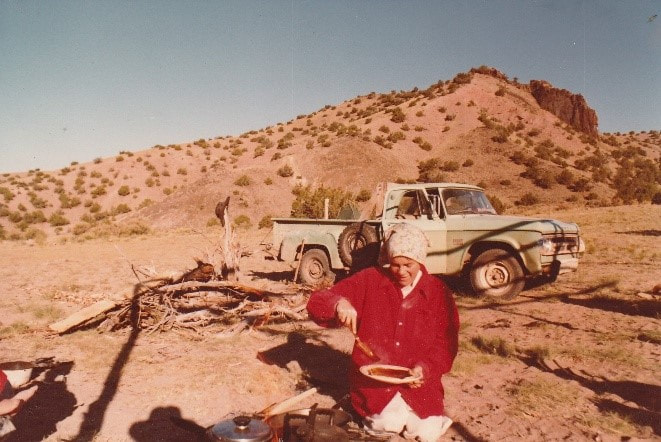

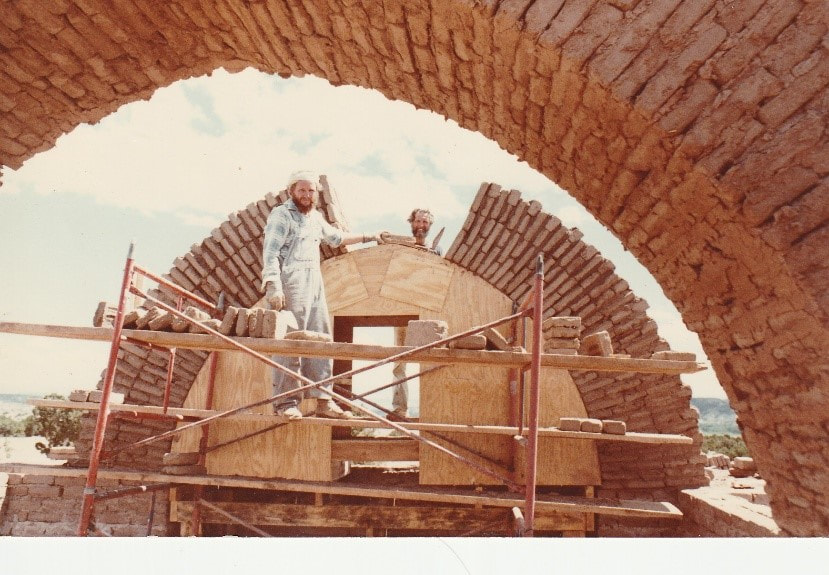

By Karima Alavi My last article, The Search for a New Home, recounted the quest for just the right place to build a mosque, and the purchase of Abiquiu land that had previously been used for cattle ranching. Having obtained the land, a small group of American Muslims were determined to situate the mosque at the center of the mesa overlooking the Chama River and Abiquiu pueblo. Once the center was marked, the next step was the actual construction of the mosque which was the first building to go up as part of a plan to eventually create a school, a retreat center, homes, and businesses on the site. The designer hired for this project was Hassan Fathy, the Egyptian architect revered for his dedication to bringing back traditional mud construction as opposed to the use of western architectural designs and materials. To facilitate the construction of the Dar al Islam mosque two men, Nooruddeen Durkee and Omar Cashmere traveled to Egypt to study ancient adobe-brick construction with several Egyptian masons. Accompanying them was Nooruddeen’s wife, Noora Issa. They returned to New Mexico with a treasure—Mr. Fathy’s architectural drawings. The next item that needed attention was to gather a crew of Muslims and non-Muslims to begin the first step of construction: laying the foundation. Local workers were hired, with Dexter Trujillo being the first non-Muslim to join this remarkable enterprise. The most critical part of building a new structure is laying the foundation. A seemingly small miscalculation can prove disastrous later on. These young builders, many of them with construction experience, some of them learning as they went along, were ready to start. There was, however, a significant issue to consider. Something that could be seen as a challenge, or as a blessing, depending upon the level of one’s determination and religious fervor. Construction was set to begin during one of the holiest months of the year for Muslims, Ramadan. (Which will be the focus of my next article.) This time of fasting, extra prayers, and religious reflection follows the Islamic lunar calendar of 354 days and hence, makes an annual shift of 11 days. In 1980, Ramadan stretched from mid-July to mid-August, the hottest time of the year in New Mexico. Undeterred, even spurred on by what was seen as an auspicious time to bore the first shovel into the ground, the young, excited Muslims moved ahead with digging the foundation. By hand. No backhoes for these folks. They were determined to work with traditional construction methods, using picks and shovels the way mosques had been built for centuries. Fasting during Ramadan meant that the Muslim workers could have nothing to eat, or drink, during daylight hours. In those long thirsty summer days, beneath the unforgiving New Mexico sun, one discovery offered these people relief: a large metal water trough left over from the days when this property served as a cattle ranch. They rigged up a long black pipe that sourced water from a wind-driven pump on the land, and filled the trough. When the heat became unbearable, the workers submerged themselves in the water to cool off. In this way, they were able to make it to the evening prayers and the breaking of the fast, which moved from 8:20 pm at the beginning of Ramadan to 8:03 on the last night of the month. The crew faced an additional challenge at this time. Where would they sleep? Local people went home each night, but many workers, especially the Muslim converts from other towns, had no where to live while pursuing their desert dream. As Rahmah Lutz told me during an interview, this project appealed to those who had a strong sense of religious purpose as well as a leaning toward an alternative lifestyle. Pretty soon the obvious solution to the housing problem arose. Spend the nights outside in sleeping bags, build a small roofed ramada for shade, and cook outdoors. They even rigged up a solar-heated shower. Khadija Cashmere, wife of Omar who had traveled to Egypt to study adobe masonry, told me she alternated between staying in their Santa Fe home, and sleeping and eating on site. Pregnant, and caring for their three-year-old son, she managed to assist with cooking on a gas camp stove. When locals told her to burn cow paddies to ward off bugs she thought, at first, that they were kidding. Then she tried it. Life in the ramada became more pleasant. Another couple, Abdur Rahim and Rahmah Lutz, lived “in luxury” at the time. They had a house on County Road 155, the place they still call home. With electricity, a functional bathroom, and a telephone, the Lutzes found themselves hosting and feeding lots of wet visitors when rainstorms made the ramada and outdoor campsites uninhabitable. According to Rahmah, “We were all in a special spiritual place. This whole thing was fueled by Islam.” And food. Lots of food. It was that sort of energy and commitment that inspired workers to gather, pray, and start digging once the mesa had been leveled and the foundation was staked out. In the words of Abdur Rahim Lutz, “Building the Mosque was fun!” All was right with the world. Then…it wasn’t.

An inspector from the New Mexico Construction Regulation and Licensing Department made a surprise visit. Out came the red flag. Construction of the Dar al Islam mosque came to an immediate halt.

2 Comments

By Daria Roithmayr On December 9th of last year, Tres Semillas sold the land across from Bode’s to the Merced del Pueblo Abiquiu and Town of Abiquiu Land Grant. During the summer and fall of last year, Northern Youth Project had already been hard at work preparing a transitional interim plan for the coming season, even as community members protested the sale and tried to persuade Tres Semillas not to sell. Three short months later, NYP is in the midst of transition, as it navigates its next chapter. As the website proudly declares, the Northern Youth Project is a regional youth-centered project focused on arts, agriculture and leadership, started and run by teens for teens. NYP was created in 2009 to serve as a platform to develop in local youth those skills that will foster their personal well-being and encourage them to invest in their communities and the environment. Programming towards that end has included hands-on art, agriculture and leadership projects that honor the past and look to the future. NYP’s long and wonderful history has been the subject of many an Abiquiu News story chronicling the project’s early beginnings and important role in the community. Up until last spring, NYP had been headquartered at the Tres Semillas location and operated two youth projects: the Bridge program, which hosted 20 children ages 5 to 12, and the Internship program, which typically engaged from six to ten interns aged 13 to 21. The long-standing Internship program was home to a mix of interns, some returning and some new, coming from as far away as Nambé. These two programs were dissolved in anticipation of the sale. But new and exciting internship programs, offering new possibilities for the young adults in the program, soon came into view. In a recent interview, Executive Director Ru Stempien talked excitedly about the new internship program that NYP has put into place even as the organization explores and plans for the longer-term future. “This past summer and fall, NYP created a partner-based internship program that shared resources and responsibilities with two regional partners who have extensive experience working with youth. One intern has been placed in Chimayo with Pilar Trujillo at her farm Viva Vida Botánica. This farm integrates traditional and modern regenerative stewardship practices to provide remedios (Botánical remedies), nourishment, and educational experiences for the surrounding community.” Stempien explained that the Viva Vida Botánica internship is training youth in traditional farming methods that produce botanical remedios, like elderberry syrup. Interns are trained in acequia-based flood irrigation, the planting and growing of perennial herbs, and in the running of a small farm business that is also deeply connected to and engaged with the surrounding community. Stempien went on to describe the second partner-based internship. “Two other interns were placed in Ojo Caliente with Don Medina and Valerie Archuleta at their small farm called OnePea Pod Farm. At this location, interns were trained in the running of an animal husbandry and farming operation: they participated in animal care and husbandry, learning how to butcher sheep and chicken and how to process hundreds of pounds of fruits and vegetables for subsistence and for sale.” Partner Don Medina is thrilled with the progress that interns have made. “They seemed to enjoy being fully immersed. All the decisions made have had their input and I believe that has made them more confident and comfortable. They have watched every plant start, seeing how long it takes in different methods, for example in cups or in seed trays or in the dirt or in a greenhouse setting and figuring which ways they prefer to do it. They were the ones who convinced us to milk again this year.” Don and Valerie have recently moved back to family land in Chimayo and are doing subsistence farming; they will be selling with the interns’ help at a local farmers market in the north this season. I asked whether the program’s partners had experience working with youth and young adults. “Yes, they have so much experience and are lifelong partners of the program,” Stempien told me. “In addition to NYP, Pilar Trujillo has worked with the New Mexico Acequia Association’s amazing youth program. Like Pilar, Don Medina and Valerie Archuleta also have extensive experience with youth, having worked previously with the Pojoaque Boys and Girls Club.” Stempien took great pains to highlight the new and exciting opportunities made possible by a partner-based internship. “With both OnePea Pod and Viva Vida Botánica, interns have been trained and mentored and participate in the actual running of a small business. Interns help farmers make the decisions that connect to marketing, planning, and strategic engagement of consumers. For example, the interns had helped with OnePea Pod farm’s farm-to-table partnership during the period that the farm was partnered with Dolina Café and Bakery in Santa Fe. The opportunity to work alongside mentors and elders on a real working farm is what makes this opportunity so special and unique.”

She also noted that all three of the interns working with partners are aged 17 and older, and are long-time interns with NYP who have gone to college. “These partner-based internships are essential for the 17-21 age range, providing support and training to these young adults as they transition from the teen program to make longer-term decisions about their futures. The partner-based internships provide them with much more integrated and direct mentorship and training on a full-time working farm and small business. This is a win-win for mentor and mentee. Young adults need mentoring and training and farmers need the help of the next generation to keep their businesses going!” I asked whether NYP saw the partner-based internship program as something NYP would continue even if it went back to a place-based operation. “Yes,” she answered. “NYP plans to work with these partners to explore the possibility of developing a more formal pilot program for partner-based internships, figuring out how to choose new partners and how to pair them with interns in a way that ensures a meaningful and successful experience for both intern and partner. This model could really work well in a lot of different communities!” On the arts front, NYP is in early discussions with a range of potential partners to develop programming for teens. For example, NYP has been in contact with Pueblo de Abiquiu Library and Cultural Center’s Andi Manzanares to begin to explore possibilities for collaboration. What is the longer-term dream for NYP? Stempien explained that the organization has its eye on the horizon, aware that it must navigate under new circumstances, not just with regard to the sale of the propoerty but also in terms of uncertainty regarding funding connected to the change of administrations in the White House. “This coming year will be an intensive strategic planning year. NYP board, staff and participants will explore whether and how the program could be ‘place-based’ again. NYP is well aware that particularly in terms of programming on leadership, there is great value in bringing together interns to create community with each other and with the community around them. At the same time, board members and staff are also aware for the need for sound infrastructure and stability to sustain a place-based operation.” Through it all, the young people themselves are leading the way, asking the important questions about the project’s future. Stempien is bursting with enthusiasm at their leadership. “Matias Coronado, this wonderful young person on our board, has centered our thinking about the future on what our participants think. We have been asking them, ‘What about this matters to you? Why do you keep coming back? What do you want to see for the next generation? What do we need to build for your younger siblings and cousins and community members to be able to come back into this work?’” For the moment, NYP is focused on community outreach and on fundraising, as it develops these exciting new opportunities that the partner-based internships present, and as the project explores the possibility of being place-based once again. Board member Patty Shure is excited about the project’s new directions and hopeful for the future. “We spent fifteen years building a project that we can be proud of. We are excited about the partner-based internship program and the board, staff and membership will be giving much thought and careful planning to what comes next for NYP!” |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed