|

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Sept. 11, 2025 Three leading animal welfare organizations—Española Humane, Santa Fe Animal Shelter & Humane Society, and Felines & Friends New Mexico—have joined forces to launch Operation Meow, a collaborative mission to support the unsung heroes caring for community cat (sometimes called feral cat) colonies across Northern New Mexico. Every day, volunteer caretakers provide food, water, and compassion to community cats. Many pay for supplies out of their own pockets to ensure these vulnerable cats stay fed, healthy, and thriving. Operation Meow seeks to ease that burden by collecting and distributing donated cat food directly to those who need it most. “Community cats are part of the fabric of Northern New Mexico, and the people who care for them are everyday heroes,” organizers said. “Through Operation Meow, we can support both the cats and their caretakers with the resources they need.” Community members can support Operation Meow in many ways:

Once we receive enough donations, we will begin the distribution process. Please monitor each organization's website for Operation Meow Updates! The mission is simple: Fix, feed, and fiercely love our community cats. Together, we can make sure every colony cat across Northern New Mexico gets the care—and the kibble—they deserve. ### MEDIA CONTACT: Española Humane: Mattie Allen, 505-423-3360; email: [email protected] Santa Fe Animal Shelter: Lex Gowans, 754-201-7924; email: [email protected] Felines & Friends: Bobbi Heller, 505-670-8823 email: [email protected]

1 Comment

Hi there! You’ll notice that this week’s post does not start with the word AUDIO, yet it still has the audio recording included. Just don’t want you to miss out! We have some changes afoot here at Zach Hively and Other Mishaps. But you’re still going to get weekly posts, including the audio voiceovers. I think you’re going to get EVEN MORE THAN THAT. Stay tuned. We had a brief moment of autumn the other day. That got me reminiscing about pumpkins, and also about my uncle, who was not (as far as I could tell) a pumpkin. I dedicated my first book of trying-to-be-funny essays to him: “For Uncle Bob, because I sure didn’t get this from my parents.” If something family-friendly can be done with a pumpkin, it has been done at the Circleville Pumpkin Show. Circleville is a small town in central Ohio whose most notable feature is that it has long housed Hivelys, thereby disproving that the Midwest is entirely bland. It also puts on the annual Pumpkin Show, a harvest festival that focuses on, you guessed it, corn. Just joshing! Corn is another Midwestern stereotype. The Circleville Pumpkin Show has focused on pumpkins, and only pumpkins, ever since the mayor started the festival in 1903. The way I read it, all the area farmers back inna day were wagoning their harvest bounty to town, and the mayor wanted to appreciate their wives’ produce. So he set up displays and established a competition for the largest pumpkin grown by a lady. Ever a visionary, the mayor also held a competition for the largest pumpkin grown by regular guy farmers, thereby striving for gender equality a full century before we still don’t have it today. Big pumpkins are the main attractions at the Show. The primary difference today is that the pumpkins are approximately the size of oxen, and they eat more, too. Otherwise, Pumpkin Show is precisely how I remember it from when I first visited it at age thirteen, except that now I know the meaning of the word “indigestion.”

Which is really too bad, because the festival carries on precisely how the mayor envisioned it more than a hundred years ago, with the world’s largest pumpkin pie, pumpkin waffles, pumpkin pizza, pumpkin ice cream, pumpkin chili, pumpkin donuts, pumpkin pulled-pork sandwiches, pumpkin cappuccinos, pumpkin kettle corn, the face-painted Pumpkin Show Man navigating crowds on rollerblades, carnival games where you can win a Taylor Swift poster, and beauty pageant competitions for the Pumpkin Show queen. The last time I visited Ohio in October, my uncle wanted me to have the full Pumpkin Show experience as an adult with access to antacids. He signed me up to sell pumpkin coffee and ride on a parade float alongside eight strangers and a roasted chicken. He took my picture under the “Most Unusual Pet” parade placard. But, despite wanting me to have the full Pumpkin Show experience, he did not enter me for the Miss Pumpkin Show competition. So, in the spirit of still striving for gender equality, here is my at-large application for next year’s crown, answering the same questions asked of my competition. Miss Pumpkin Show Application Entrant: Miss Zach Hively Age: A lady never tells! Hobbies: Doing family-friendly things to pumpkins, such as sawing them open with serrated knives, gutting them, and displaying their corpses to the neighborhood. I also enjoy consuming their flesh from tin cans. Plans after high school: Ride the bus home, eat a sandwich, probably take a nap. Favorite Pumpkin Show memory: There are so many wonderful memories to choose from! Like that time I would have won the pumpkin toss if I had forged my age to enter the kids’ twelve-and-under category. Or that time I sat on the announcement stage for a parade, and the man with the microphone kept insisting that my aunt “do the mayor when he comes by.” But I have to go with the 1998 pet parade. My uncle loaned us the gerbil tank from the school where he works. Lo, the gerbil had that very morning given birth to half a dozen babies! My sisters, my cousin, and I dragged those gerbils in a wagon through downtown Circleville, and when we returned to the staging area, there was only the mama gerbil left. And boy, was she stuffed. Somehow, we did not win the Most Unusual Pet category. As Pumpkin Show queen, I will institute a Greatest Attrition category for all future pet parades. Favorite thing to do at the Pumpkin Show: Once again, there are just so many choices. But I would have to say my favorite activity is eavesdropping. Eavesdropping? What do you hear? I can’t tell you! That would be rude. Besides, this year’s Baby Parade entrants really aren’t as ugly as people said. What qualities do you have that you believe would make you successful as Miss Pumpkin Show, if chosen for the honor? Diversity. I would be the first queen to break countless, possibly up to a dozen, glass hurdles. I’d be the first queen with an unplucked beard, and the first on this side of twenty. A real Jackie Robinson in the realm of Pumpkin Show queens. How would you describe Pumpkin Show to someone who has never experienced it before? Well, I described it already, so instead, I’d like to offer a new slogan suggestion. The Circleville Pumpkin Show: Come for the pumpkins, stay for them too! And ladies, please keep your distance from the mayor.

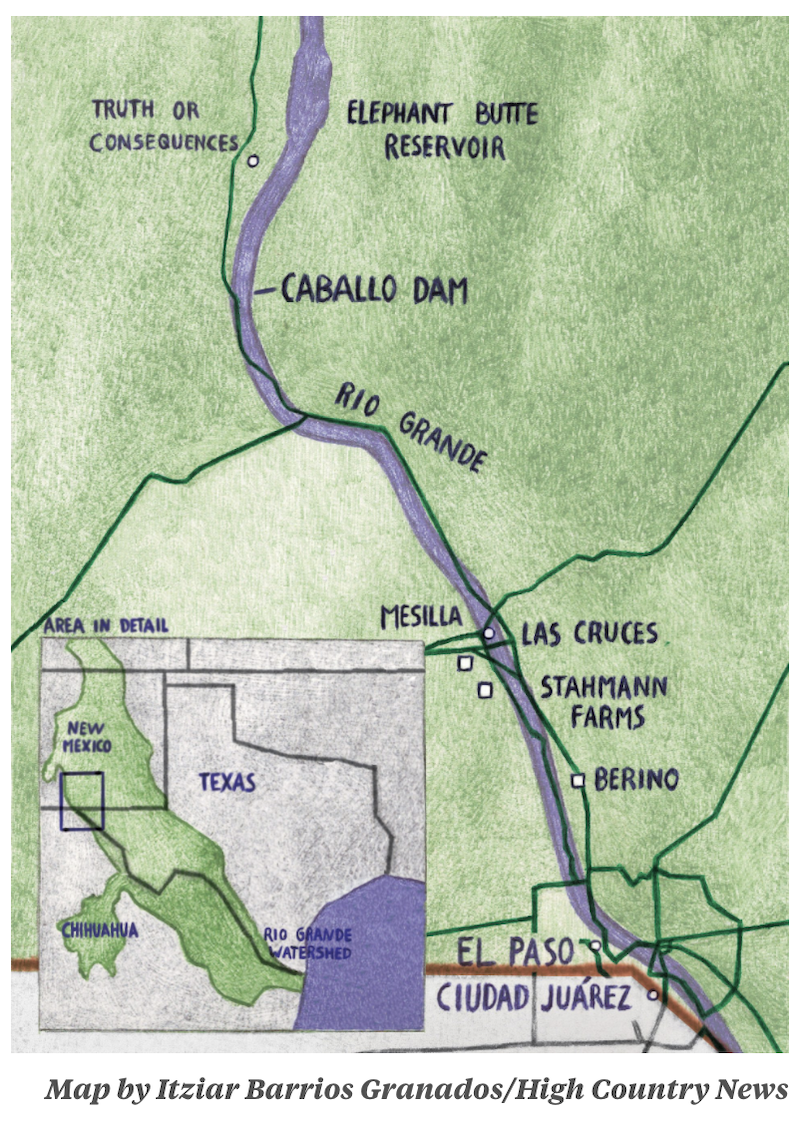

Green is not the color one expects to see in the cactus-and-yucca-dotted Chihuahuan Desert of southern New Mexico. But for more than a hundred miles along the I-25 corridor, between Truth or Consequences and the Texas border, a rich vein of greenery runs through the endless sea of beige.

It’s a cultivated woodland made up almost entirely of a single species — Carya illinoinensis, the pecan. Native to the lower Mississippi Valley, the trees were imported here, to the Mesilla Valley, in the early 1900s. In those early years, they were planted sparingly; the average precipitation is a scant 9 inches per year, hardly enough to sustain this Eastern hardwood. It wasn’t until after 1916, when the Rio Grande Project and its centerpiece, Elephant Butte Dam, were completed, that the trees began to flourish. Below the dam, the river is hemmed into a narrow channel between levees, and nearly all of its flow is shunted into a vast network of irrigation canals. The transformation has been staggering: In 2018, just over a hundred years after the completion of the Rio Grande Project, New Mexico surpassed Georgia as the nation’s leading pecan producer, a title it has retained off and on to the present day. Much of that agricultural production comes from this dry basin in Doña Ana County, near the Texas border. On a 95 degree day in late May, I met Rafael Rovirosa, whose family has been growing pecans in New Mexico since 1932. Today, the Stahmann family has 3,200 acres of pecan trees in some of the richest farmland along the Rio Grande River. We met in the parking lot of one of Stahmann Farms’ pecan-processing plants south of the town of Mesilla. Rovirosa threw open the door of his pickup. “Let’s go for a ride,” he said, and we set out for the pecan groves. Rovirosa is lean, with deep-set eyes and dark stubble. He looked more like an academic than the operations chief of an agricultural outfit the size of a small city. He piloted his truck through a maze of roads leading into one of the oldest groves in the valley. Some of the pecans were 45 feet tall and close to a century old, planted in perfect rows spaced 30 feet apart to maximize yield. A luxuriant carpet of grasses below the lush canopy gave the orchard the feel of an East Coast hardwood forest. “Some people might say this isn’t the most efficient way to grow pecans, that they ought to be trimmed back,” said Rovirosa. The lower limbs scraped the top of his pickup. “I don’t care. I think it’s beautiful.” The region has paid a steep ecological price for this agricultural abundance. Beside us as we drove, I could see a shallow, concrete-lined irrigation canal carrying a steady flow of water, clear as a mountain stream. In many places, water pooled around the bases of the trees; flood irrigation is still standard practice here. Pecans are prodigious water guzzlers. A single mature tree — which can produce 50 or more pounds of nuts in a season — requires around 30,000 gallons of water per year. In southern New Mexico, over 50,000 acres are currently in production. New Mexico pecan farmers have become the state’s largest single agricultural water user, slurping up an estimated 93 billion gallons per year — enough to supply a city of around 3 million —according to a 2023 report by Food and Water Watch. Some of the farm’s soils, Rovirosa noted, are sandy, and water is absorbed very quickly, meaning that it must be applied frequently. “This actually isn’t necessarily a bad thing,” he said. “We want the water to percolate down, because that’s how we recharge the aquifer. Agriculture is the number-one recharger of the aquifer when times are good.” But times aren’t good. Mired in a nearly 25-year-long drought, the Rio Grande, one of the great rivers of the West, wends its way through pale desert just beyond the western edge of these verdant groves. And for the last nine months, it has run completely dry.

DESPITE ITS NAME, the Rio Grande is not a large river; its average annual flow, which derives mostly from distant snowpack in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, is less than one-sixth that of the Southwest’s other great river, the Colorado. But more than 13 million people in Colorado, New Mexico and Texas — and across the border in Mexico — depend on it for drinking water and other uses. It also irrigates over 2 million acres of farmland. For centuries, small-scale subsistence agriculture was the only kind of farming practiced in this dry and unforgiving region. Spanish settlers created communal water systems called acequias that sustained a patchwork of small farms throughout Nueva Mexico.

Before the Rio Grande Project, the river sometimes ran dry, though seldom for extended periods. Today, however, during the few months when there is water in the riverbed, it has been released from upstream dams. Most of it is sent downstream to Texas to meet New Mexico’s obligations under the Rio Grande Compact, a water-sharing agreement between the two states and Colorado that was signed into law in 1939. Under this agreement, New Mexico is obligated to send 47% of the water it receives at Elephant Butte Reservoir to Texas. In 2013, Texas sued New Mexico, alleging that groundwater pumping by the state’s farmers had compromised the flow of the river. (Groundwater pumping near a river can draw water away from it.) The Rio Grande’s flow, when it exists, is not nearly enough to supply the Mesilla Valley’s commercial farmers. To make up for the surface water deficit, pecan (and alfalfa) growers pump groundwater at a ferocious clip, dredging up millions of gallons last year alone — vastly exceeding nature’s ability to replenish it. That water use is a stark display of economic power. Last year, the growers generated an estimated $167 million in revenue, making pecans the largest food crop in New Mexico. In the mid-2000s, local farmers mounted an aggressive campaign to export the nuts internationally, including to China, which at the time still lacked a word for this uniquely American tree-fruit. Today, China remains a key destination, but most of the nuts go to Mexico, where they’re de-shelled, packaged and then shipped back to the United States for export or domestic sale. (Rovirosa’s family orchard does its own shelling.) The harvesting is done almost entirely with machines, and few laborers are required. Little of the profit goes to benefit the local economy. There are also biodiversity costs. By the start of the 21st century, several species of fish, including the shovelnose sturgeon, longnose gar, American eel, speckled chub and Rio Grande shiner, had become rare in the river below Elephant Butte Dam, or been extirpated altogether. The bosques, vast willow and cottonwood forests in the river’s wide floodplain, once provided tens of thousands of acres of habitat for birds, reptiles, insects and fish. The wetlands and riparian woodlands also offered flood protection and a buffer against drought. Today, several endangered animals — including the southwestern willow flycatcher, western yellow-billed cuckoo and New Mexico meadow jumping mouse— cling to existence in the few remaining pockets of native forest and grassland.

As of May 1, snowpack in the river’s headwaters was projected to provide only 12% of the water it normally does. Elephant Butte Reservoir was only 14% full on April 18, and water managers at the Elephant Butte Irrigation District, or EBID, announced that allocations would be cut by 83%. Instead of a full allotment of 3 acre-feet, farmers received a mere 6 inches. At the end of May, roughly 5,000 acres of farmland had been fallowed across the district under the state’s Groundwater Conservation Plan. Throughout the valley, dry fields with pale soil and withered stalks of chile, onion, alfalfa and cotton hinted at the row crops that have been lost. (Perennial tree crops like pecans cannot be fallowed; without water, the trees perish.) In April, the USDA’s Farm Service Agency declared a state of emergency for 15 New Mexico counties and announced that it would offer emergency loans to local farmers, ranchers, and dairies.

The river’s condition when it reaches Elephant Butte Reservoir is the byproduct of environmental, infrastructural, managerial and political factors largely beyond the irrigation district’s control. For example, under the Rio Grande Compact, Colorado farmers — many of them alfalfa growers in the San Luis Valley — are allowed to divert between 30% and 70% of the river’s flow, depending on snowpack, before it crosses the state line. Today, the river carries a much smaller volume of water on average than it did before European settlement. Downstream, Texas is not only embroiled in a legal battle with New Mexico, it’s also fighting with Mexico over its failure to meet the terms of an 81-year-old treaty requiring Mexico to deliver an average of 350,000 acre-feet of water to the U.S. annually over a five-year period. Mexico, facing the same extreme drought as New Mexico, hasn’t delivered its share to Texas via the Rio Conchos, the Rio Grande’s largest Mexican tributary, and is now nearly 400 billion gallons in arrears. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, R, has echoed the Trump administration’s confrontational posture, declaring in a press release last November that “Mexico’s blatant abuse and disregard of water obligations … must not be allowed to continue.” The Bureau of Reclamation predicts that the Rio Grande watershed will continue to warm and dry, losing as much as one-half of its hydroelectric capacity by the end of the century. Many climatologists say that “drought” is no longer the right word for the situation: “Aridification” more accurately describes the massive ecological shift afoot in the Southwest. Dust storms, once infrequent, now turn the sky an eerie ruddy brown, blotting out the sun. Several times this spring, blowing dust scoured from desiccated, overgrazed desert soil closed highways across the region. “We are starting to see a shift in the weather patterns,” said Ryan Serrano, the Rio Grande manager of the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission, which oversees the state’s water resources. More troubling, the monsoonal rainstorms, which once came reliably between mid-June and late September, delivering the bulk of the region’s annual rainfall, are not materializing as they once did. “We’re either not seeing the monsoon rains, or they come later and later in the season, when it’s not the most ideal time for that to happen.” And there are larger questions about the sustainability and equity of a system that has all but erased a major river while delivering the lions’ share of its water and profits to a handful of wealthy and influential farmers. “They’re still flood irrigating, but they’re not feeding us anymore, and they’re not employing us,” said Israel Chávez, an activist and attorney whose family has lived in the Mesilla Valley for generations. “The state heralds it as a boost to the economy. But when no one can be employed, and when no one can eat any of this, then it begs the question: Who is this for?”

IN MAY, I attended EBID’s monthly board meeting in Las Cruces. The conference room was decorated with black-and-white photos showing Elephant Butte Dam’s construction. The proceedings opened with the Pledge of Allegiance and a prayer led by Gary Esslinger, EBID’s treasurer-manager from 1988 to 2024.

“Father God,” he said. “Please send the rains.” Few people know the inner workings of the district’s sprawling, complicated plumbing system, which delivers water to close to 7,000 farmers across roughly 90,000 acres via 357 miles of canals, as intimately as Esslinger does. The next day, he drove me south along Highway 28, past Mesilla’s adobe square and into the verdant heart of pecan country. The orchards were a beehive of activity. White pickups bearing EBID’s insignia swarmed; the “ditch riders,” as Esslinger called them, were preparing the canals to receive an upcoming release of water from Caballo Dam into the Rio Grande and its system of canals. Esslinger doesn’t believe the doomsday climate talk. Drought is part of a cycle, he said, and the wet years will return. He sees the current situation as a temporary setback — a management problem to be solved. The first order of business, he said, was to make the irrigation system more efficient, mainly by replacing the old dirt-lined canals with large underground pipes to reduce seepage and evaporative losses. “We’re, like, only 55% efficient, and that’s not good when you’re in a drought scenario,” he said, gesturing to the groundwater gushing into a dirt ditch from a candy cane-shaped pipe. Along its edges grew Equisetum arvense, a weed better known as horsetail, which, he said, can quickly overwhelm a canal. Much of the water loss in the Mesilla Valley happens even before water reaches the ditches. Several studies have found that Elephant Butte Reservoir loses around 140,000 acre-feet per year — roughly 6% of its maximum capacity — to evaporation. The loss would be staggering in any agricultural region, but in one suffering through a 25-year drought, it is existential. “The state heralds it as a boost to the economy. But when no one can be employed, and when no one can eat any of this, then it begs the question: Who is this for?” Esslinger said there was a larger strategy here beyond repairing leaky canals. The updates, he said, will make the system less reliant on Rocky Mountain snowpack and better able to capture water from monsoonal storms and the remnants of the tropical storms and hurricanes that sporadically hit the valley. “We have 300 miles of drainage canals here, and they’re cut 30 feet deep,” said Esslinger. “That’s a lot of storage, if you think about it. It’s just a matter of trying to adapt the canal to receive flood water instead of irrigation water.” By strategically installing a series of pumps, Esslinger believes that the district can capture the stormwater that, in the past, was simply shunted into the river channel. “Our drains are connected to the groundwater table, and so it’s a great way to recharge the aquifer,” he said. Doing so effectively, however, requires being able to predict where and when the storms will hit and then quickly evacuating water from the canals to prevent flooding. “We need to modernize our systems, to know when these storms are going to be able to hit in advance,” he said. Despite Esslinger’s technocratic optimism, the unspoken message was one of desperation. As snowpack fades in the Southern Rockies, the irrigation district will become increasingly reliant on the summer storms that, in the drying climate, have become less dependable.

Paying for these kinds of large-scale fixes has also become far more uncertain under the Trump administration. Federal allocations authorized under President Joe Biden have halted, and DOGE-led firings and resignations have paralyzed federal agencies, leaving the district’s funding in bureaucratic limbo. A $15 million infrastructure improvement allocation awarded to the district by the USDA in 2024 has yet to be dispersed. “I just don’t know what happened to that money.”

Esslinger showed me a centerpiece of the district’s infrastructure improvement plan: a network of canals around the antiquated Mesilla Dam, which sprawls like a concrete battleship across the Rio Grande’s dry riverbed. The scheme utilizes a series of small channels called spillways that are cut perpendicularly into the riverbed and designed to return water to the river in emergencies. “In a flood event, ditch break, a car in a canal, any event where you’ve got to evacuate water, you have to have these spillways available,” he said. Esslinger says these safety valves have a unique feature: When there’s water in the river, it backs up at Mesilla Dam and fills the spillways. “It just sits there,” he said. “And so, I was thinking, what if I put pumps in these spillways and lifted the water out of the river and into the canals? That would save 40 miles on the delivery of water.” Esslinger has done just that, installing two large submersible pumps in the canal. When they’re operational, he said, the district will be able to pull water from the spillway and fast-track it to local farms. The design, I thought, seemed to show that EBID’s leaky, antiquated irrigation system could be vastly improved simply by allowing water back in the river. But Esslinger balked at this assertion. Allowing any “extra” water to flow downriver out of the district toward Texas, was, to his mind, unimaginable. “People moving here from places where there’s water — Idaho, Ohio, Iowa — ask, ‘Where the hell’s the river? It’s a public good, isn’t it?’ And I say, ‘No, it’s not public water. It’s paid for by the farmers.’” (EBID members pay $100 for 2 acre-feet, according to Esslinger.) It seems that decisions about whether the Rio Grande is a river or a sand trap are not left to scientists, the public or even politicians, but to the Elephant Butte Irrigation District and its largest agricultural clients.

“I DON’T CONSIDER them farmers at all,” Israel Chávez, the Las Cruces attorney and activist, told me. “Farmers feed people. Pecans aren’t feeding anyone (here). They’re a luxury crop that are non-native to this area.”

We climbed into his cluttered Prius, driving 20 minutes north to the small town of Doña Ana, where Chávez grew up. On the town’s outskirts, we merged onto the El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, which once connected Mexico City and Santa Fe. An old weed-filled ditch, completely dry, paralleled the road. Chávez said this canal was part of the town’s original acequia system, which carried water from the Rio Grande to small local farms. Founded in 1843, the village was named for Doña Ana Robledo, a Mexican colonist who died fleeing the 1680 Pueblo Revolt in northern New Mexico. The small, dusty community sits atop a small bluff. One- and two-story adobe buildings, many in disrepair, radiate outward from a central square. We walked past a bronze statue of the town’s namesake pouring water from a bucket into two clay vessels. He remembered running through nearby green fields as a child. “Any type of vegetable you can imagine was planted across the street from my house,” he said. He gestured to the floodplain and what was once a bosque, where a sprawling orchard now sidled up to the edge of the hill. “All those fields have been replaced with pecans.” Chávez said his paternal grandfather came to the Mesilla Valley from Mexico in the Bracero Program in the 1950s. “He was able to work for a farmer who was growing all sorts of things, and that farmer ended up giving him some land and letting him grow on his own parcel,” he said. That kind of arrangement is rare in the era of industrial-scale pecan farming, Chávez said. “We have seen a major downturn in labor. I don’t think that that’s happening in a vacuum.” “People moving here from places where there’s water — Idaho, Ohio, Iowa — ask, ‘Where the hell’s the river? It’s a public good, isn’t it?’ ‘No, it’s not public water. It’s paid for by the farmers.’” The high cost of farmland coupled with the scarcity of water rights — and water itself — has not only kept new pecan farmers from entering the arena, Chávez said. It has also crowded out smaller farmers growing seasonal row crops — onions, beans, corn, squash and chiles, the most famous of which come from the nearby town of Hatch — on smaller plots of land. Yet some farmers are still trying to gain a foothold and redefine agriculture in the valley. Ryan Duran works with her partner and his family on Big Moon Farms, their 13-acre plot near the town of Berino, 30 minutes south of Las Cruces. Their list of crops is extensive: collard greens, Swiss chard, broccoli, carrots, radishes, onions, garlic, okra, corn, calabash gourds, melons, beans and several different types of chiles. “It’s hard work because things are coming up at different times,” she said. “Some things don’t make it. Some crops fail because it’s too hot.” Big Moon, she explained, gets a little surface water from EBID, but it’s a drop in the bucket compared to what commercial-scale pecan farmers receive. Unlike the region’s pecans, Duran said the crops grown on her farm are consumed locally. “The government is trying to pay farmers not to farm, to conserve water, which is concerning,” she said. “We should be protected. We shouldn’t have these giant orchards taking all the water.”

SPRING RELEASES OF WATER from Elephant Butte Dam are used to meet New Mexico’s water-delivery obligations under the Rio Grande Compact. Rather than a single sustained release, said Tricia Snyder, rivers and waters program director for the environmental group New Mexico Wild, regulators should allow more consistent water releases throughout the year to mimic the natural cycles the large dams have erased.

These “environmental flows”— most of which occur in the upper and middle reaches of the river above Elephant Butte and the Rio Grande Project — are meant to emulate the spring snowmelt and summer monsoon runoff before the infrastructure was built. “The plant and wildlife communities that have evolved around this river depend on that timing,” she said. “So how do we approach that, given the realities of climate change?” The river below Elephant Butte, Snyder said, needs to be managed with its many shareholders, both human and non-human, in mind. “We might say, OK, agriculture needs this much water at this time, and this species may need a pulse flow at this specific time of year. There are different needs. So how do we tie those all together to meet as many of those needs as possible?” Others hope to restore the river’s lost bosques and wetlands. Not only do riparian zones provide critical wildlife habitat, they also aid with water storage and floods, like the one that struck this stretch of the Rio Grande in 2006, devastating cities across southern New Mexico and West Texas. After storms dumped up to 30 inches of rain, floodwaters overwhelmed man-made drainage systems, washing away roads and buildings. Restored riparian zones could act as buffers, slowing down water and spreading it more evenly across the floodplain. Vegetated areas also improve a river’s “baseline” flow, releasing water into the channel slowly throughout the year, even during the dry season. One such riparian restoration project is underway 20 minutes northwest of downtown Las Cruces on a 30-acre experimental plot known as the Leasburg Extension Lateral Wasteway #8 Restoration site. Here, a small forest of willows, cottonwoods and native shrubs is taking shape. The project is overseen by the International Boundary and Water Commission, or IBWC, the agency within the U.S. State Department that oversees waterways shared by the U.S. and Mexico.

The Leasburg site, one of 22 being managed by the IBWC, is the product of a 16-year collaboration between the federal government, local water managers and conservationists to enhance habitat along the Lower Rio Grande. Between 2009 and 2021, IBWC planted over 122,000 native trees and shrubs and removed thousands of invasive saltcedars across its sites. “At first there was some pushback among farmers,” said David Casares, general operations supervisor with the IBWC, who is overseeing the restoration. “They didn’t understand what we were doing here. But once they saw it, they learned to accept it. The way EBID sees it, we’re farmers, too — farmers of native trees.”

Though the Leasburg plot is small, the birdsong and the rustle of leaves are potent reminders of a lost Rio Grande. Indeed, this is as close as one can come to the verdant bosques that once lined the river for hundreds of miles. These small islands of restored native biodiversity, most of which are off-limits to the public, comprise roughly 500 acres, and a dozen of them have been managed to create habitat for a species that has come to epitomize the destruction of the lower river’s riparian ecosystems: the endangered southwestern willow flycatcher, a small songbird that once thrived in the riverside wetlands and forests. Surveys by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation have found the birds at or near several of IBWC’s sites. When I visited, two IBWC workers were hacking at vegetation with rakes and hoes in several small canals, preparing for the release of water from Caballo Dam and wanting to ensure that nothing would impede its flow to the trees. (The IBWC, like the surrounding farms, bought water rights from the Elephant Butte Irrigation District and was waiting for the upcoming agricultural releases.) The water couldn’t come soon enough. A closer look revealed that the small cottonwoods, no more than 15 or 20 feet tall, showed signs of water stress. Their leaves, which should have been a vivid green, were a pallid greenish yellow. Mature cottonwoods with their extensive root systems can withstand successive dry years, but young cottonwoods need a steady water supply. But Casares was confident that the trees and grasses would survive, even with this year’s limited water allotment. “Once we start irrigating, the water tables go up,” said Casares. “These are small areas, but they are having a big impact.” RAFAEL ROVIROSA, whose family has profited from pecans for generations, said he is also seeking solutions. As we drove through his family’s pecan grove, he told me that the current situation, in which surface water deficits are covered by water pulled from shrinking aquifers, is clearly unsustainable. “If the wet years don’t come for another decade, we might be OK,” he told me. “If the wet years never come again, then there needs to be drastic changes in the way that we use water here.”

We left the green grove and drove into the desert. In the hazy distance, the Organ Mountains jutted into the ruddy sky. We passed a small fallowed plot and reached a field covered in tightly spaced rows of tiny trees. They were pistachios, not pecans, something Rovirosa is just beginning to experiment with. Some of the leaves were dry and brown around the edges. But he thought it was only cosmetic, an unsightly but ultimately harmless drying caused by the winds that rake the valley. The trees, he said, were taking hold.

Pistachios require less water and are more salt-tolerant than pecans. Rovirosa also said that he thought they were more popular with U.S. consumers than pecans. In this plot and another one a few miles down the road, Rovirosa was experimenting with two other varieties of trees — a species of Spanish oak and an Italian pine. Their bounty is not found aboveground but in their roots: Both species are hosts for truffles, which Rovirosa says can bring more than $300 per pound. If Rovirosa can fine-tune these higher-value crops to grow in the desert, he can bring in more money per acre with less water. “I don’t know if it’s going to work,” he said. “It’s been a challenge to keep the trees going. They love the summer. They’re fine in the winter. But they die in the spring.” He cracked a little smile: “But this time it seems like we got it right.” He said he’s taken some heat from older farmers for branching out and searching for crops that might thrive better in a drier, hotter climate. “People get used to doing things a certain way,” he said. “It’s on me to figure out how to do it so that I can show everyone else how.”

Rovirosa’s main insurance policy, however, involved looking for farmland elsewhere. “One of my long-term goals has been to start to diversify geographically,” he told me. “It’s hard to pick a good place. They say the Southeast is going to get destroyed by hurricanes and the Southern Appalachians are going to get devastated by floods.”

But he thought he’d found the place, located in another besieged agricultural region: California’s Salinas Valley, the Steinbeckian refuge of Dust Bowl refugees in decades past. “I think the Salinas Valley gets a little bit more water than what they get in Spain,” he said. “The temperatures are about the same. So I don’t think that they would need that much water there, just a little bit of supplemental irrigation in the summer, and that’s it.” Rovirosa added: “It’s absolutely beautiful there,” he said. “We’ll see.” Funding for this story was provided by the University of Colorado’s Water Desk. We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at [email protected] or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy. This article appeared in the September 2025 print edition of the magazine with the headline “The Pecan Problem.” Sep 8, 2025 | Press Releases SANTA FE — Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham and the New Mexico Early Childhood Education and Care Department announced a historic milestone on Monday: New Mexico will become the first state in the nation to guarantee no-cost universal child care starting Nov. 1. This groundbreaking new initiative will make child care available to all New Mexicans, regardless of income, by removing income eligibility requirements from the state’s child care assistance program and continuing the waiver of family copayments. “Child care is essential to family stability, workforce participation, and New Mexico’s future prosperity,” said Lujan Grisham. “By investing in universal child care, we are giving families financial relief, supporting our economy, and ensuring that every child has the opportunity to grow and thrive.” This announcement fulfills the promise made by the governor and the New Mexico Legislature when they created the Early Childhood Education and Care Department in 2019. Since then, New Mexico has expanded access to no-cost child care to families with incomes at or below 400% of the federal poverty level, reducing financial strain on tens of thousands of families. With Monday’s announcement universal child care will be extended to every family in the state, regardless of income. This amounts to an average annual family savings of $12,000 per child. “New Mexico is creating the conditions for better outcomes in health, learning, and well-being,” said Neal Halfon, professor of pediatrics, public health and public policy at the University of California, Los Angeles, and director of the Center for Healthier Children, Families, and Communities. “Its approach is rooted in data, driven by communities, and becoming a model for the nation. “By prioritizing public investments in early childhood educators, families, and children, New Mexico continues to lead the way in building a sustainable, affordable, and quality child care and early learning system that helps its communities and economy thrive,” said Michelle Kang, president and CEO of the National Association of the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). “Achieving universal child care will make a huge difference for the state’s children, families, businesses, and educators—and for all of us, by showing that it can be done.” Families who receive child care assistance report greater financial stability, more time to focus on their children, and the ability to choose higher-quality care settings. Now, every family in New Mexico will have the same opportunity. New Mexico is also taking decisive action to build the supply of infant and toddler care statewide:

Programs that commit to paying entry-level staff a minimum of $18 per hour and offer 10 hours of care per day, five days a week, will receive an incentive rate. New Mexico estimates an additional 5,000 early childhood professionals are needed to fully achieve a universal system. “Early childhood care and education is a public good,” said ECECD Sec. Elizabeth Groginsky. “By providing universal access and improving pay for our early childhood workforce, we are easing financial pressure on families, strengthening our economy, and helping every child learn in safe, nurturing environments. This is the kind of investment that builds equity today and prosperity for the future.” With universal child care, New Mexico is leading the nation by showing that what is best for children and families is also the smartest investment for long-term prosperity—building a stronger future for every community in the state. For more information about how families and providers can access universal child care benefits, visit and toolkit: ECECD Universal Child Care Resources Page. Courtesy of Tim Seaman and Glenna Dean Culinary apple varieties are now ripening in our orchard. It's easy to make a good pie with most any store-bought apples, and most everybody has apples on their own trees this year in and around Abiquiu, but you might be surprised at the difference these old time apples make in your baking. Many of the best American pie apples are simply unavailable because they are difficult to grow, low yielding, don't travel well, or are just plain ugly.

We will be bringing these apples to the Abiquiu Farmers Market through October where you can sample and compare them for use your best recipes. Our apple varieties vary in their culinary properties. They can remain firm or soften into a custard when baked. They can emphasize sweetness or tartness, or both (best). If you want to make a visually pleasing pie like the pictured gallete, you may want to choose larger, symetrical apples. If apple cobbler or crisps are on the menu, look for the small-to-medium sized apples. Some of the best culinary apples have uneven or russeted skins so you might want to peel them (we don't). Some say the ugliest apples have the best taste, and store better through the winter months. We will continue bringing crisp eating apples to market as long as they last, but as the days shorten and we pick the highly flavored varieties, some apples develop extra sweetness when left on the tree, especially after an early frost or two. These are our favorites and we really don't want to sell them so we might have to raise the prices. We call these flavor bombs. We may also bring some tangy apple juice (aka cider) to market in 1 gallon containers. Tim Seaman and Glenna Dean Manzanar los Silvestres 21581 US 84  Los Alamos National Lab Team Leader for Radioactive Air Emissions Management Dave Fuehne in front of an air monitoring system during a media wildfire preparedness tour on May 28, 2025. Lab officials will be allowed to release a radioactive gas into the air as soon as this fall, following approval from state environment officials on Sept. 8, 2025. (Courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory) New Mexico environment officials on Monday gave permission for Los Alamos National Laboratory to vent a radioactive gas within the next six months.

The decision came on the heels of federal officials urging the state in a recent letter to make a decision, and pushback from anti-nuclear and Indigenous groups about the proposal. Specifically, LANL aims to vent four waste containers filled with tritium and hazardous waste that it packed in 2007 and left at the lab’s disposal site, called Area G. In 2016, LANL officials discovered the drums were building pressure and could potentially explode. In a worst-case scenario modeled for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — which the lab said was unlikely — a rupture of all four containers could expose people to a dosage of 20 millirem, double the airborne radiation limit that LANL is allowed to release for all operations for a whole year. Tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, can be naturally occurring or a byproduct from nuclear research. The EPA characterizes the gas as a lower threat, emitting radiation that often cannot penetrate the skin, and is only considered hazardous in large quantities from inhalation, skin absorption or consumed in tritiated water – a replacement of one of the hydrogen molecules with tritium. Rick Shean, Resource Protection Division director for the New Mexico Environment Department, told Source NM that state officials and U.S. Environmental and Protection Agency officials will be onsite during the planned venting across 12 to 16 days during weekends. “We will be there, us and the EPA, [so] if something does go wrong, there’s a discussion with [U.S. Department of Energy] that we can observe,” Shean said. “We’ll step in and stop it if we have to.” Among several provisions in a Sept. 8 letter from the environment department to the National Nuclear Security Administration and the lab’s contractor, environment officials will require LANL to keep the release below 6 millirems as a “hard stop limit,” which is lower than the 8 millirems LANL proposed. Shean noted that a typical release of tritium throughout the year from the lab is between zero to 1.5 milirems. Indigenous groups including Tewa Women United, Honor our Pueblo Existence and anti-nuclear groups have raised concerns that federal limits for tritium exposure levels of a of 10 millirem were based on men, not pregnant women or young children. Shean said the department’s mandate takes the concern raised by the groups into consideration. “We do understand the concern around thresholds being put out there, the standards being based on typically male adults,” he said. “That was one of the reasons guiding our decision to lower the threshold to this event to six milirems.” In addition to the concerns about exposure levels, anti-nuclear activists and Indigenous groups also recently raised objections about what they described as restrictions on public participation and transparency at a recent meeting on the proposal. The state environment department previously set four conditions for NNSA and Triad to meet for approval, including a public meeting and tribal consultations. The Sept. 8 letter concludes with an admonishment from state officials, saying the operation is necessary because of LANL’s “failure to properly manage hazardous waste at the time of generation followed by almost a 20-year disregard of compliance obligations under state laws and rules,” the letter said. In a statement Monday, National Nuclear Security Administration Public Affairs Specialist Toni Chiri said laboratory officials will be in contact with Congressional, state, local and tribal governments to release the dates for the tritium venting expected this fall and will ensure the venting does not overlap with Pueblo Feast days or other events. “This operation will be conducted with the utmost considerations for safety to LANL employees, the surrounding communities, and the environment,” Chiri said. “LANL engineers have done careful analysis of the controlled depressurization process and will monitor it in real-time to ensure safety.” Emails requesting comment from the nearby Pueblos of San Ildefonso and Santa Clara went unreturned as of publication. Joni Ahrends, executive director at Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety, called the release a “pattern of practice,” saying that LANL has been contaminating air, land and water in the more than 80 years since the Manhattan Project. “Who’s going to pay the price? The people of Northern New Mexico,” she said. “And there’s never an answer to the question: ‘when is it going to stop?’” NM Gov announces Oct. 1 special session on federal cuts to healthcare, nutrition, public media9/4/2025 New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham will convene lawmakers on Oct. 1 for a special legislative session, her office announced Thursday, to tackle federal cuts to Medicaid and other services, among other issues.

The governor’s office began floating the possibility of a special session even before July 4, when President Donald Trump signed H.R.1, the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” a federal spending bill that contains significant cuts to the state’s Medicaid and nutrition programs. “New Mexicans should not be forced to shoulder these heavy burdens without help from their elected officials,” Lujan Grisham said in a statement. “After discussions with legislative leaders, we’ve resolved to do everything possible to protect essential services and minimize the damage from President Trump’s disastrous bill.” The bill contains multi-billion-dollar cuts, the governor’s office said, that threaten “the survival of New Mexico’s health care system, particularly in rural areas.” The news release listed several areas that lawmakers plan to address, including:

The governor is also discussing with lawmakers whether the session will address “behavioral health challenges that affect our criminal justice system and community safety,” according to the news release. Lujan Grisham expressed dissatisfaction at the end of the regular legislative session earlier this year with lawmakers’ approach to crime and said then that she would consider a special session for that topic alone. A news release from state Senate Republicans indicated they were preparing for that possibility with legislation to address New Mexico’s “juvenile crime crisis” and hold “repeat criminals accountable.” The news release also listed legislation that would “protect the state’s ‘most vulnerable children'” and reform medical malpractice law as Senate Republican priorities. “We appreciate any opportunity to provide real solutions for New Mexicans,” Senate Republican leader Sen. Bill Sharer of Farmington said in a statement. “Just as we did during last year’s failed public safety special session, Republican legislators are prepared to address the pressing issues facing our state.” Lujan Grisham’s Communication Director Michael Coleman confirmed that legislation to ban Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention would not be on the agenda, a possibility previously mentioned by the governor’s chief counsel that prompted renewed debate on the topic among lawmakers. According to the news release, the Oct. 1 session will be the seventh special session during the governor’s tenure, which began in January 2019. 3:25 PM This story was updated following publication to include confirmation from Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham's office that legislation to ban ICE facilities in the state will not be on the agenda for the special session. Rep. Gabe Vasquez, D-NM, introduced legislation Tuesday that would provide a pathway to permanent legal status for undocumented workers in critical sectors such as health care, agriculture and emergency services.

Vasquez’s “Strengthening Our Workforce Act” would grant two-year conditional status to non-citizens who meet strict requirements and work in essential industries, according to a news release from his office. “People who work hard, follow the rules and play a vital role in our economy should never be forced to live in the shadows or in fear of mass deportation,” Vasquez said in a statement. The bill comes as the Trump administration implements stricter immigration enforcement policies that supporters say are necessary for border security, but critics argue are separating families and hurting the economy. Under Vasquez’s proposal, workers would need to have been physically present in the United States since Jan. 1, 2024, and employed in a covered profession for at least 100 days before applying. They would also be required to maintain employment for 100 days annually over two consecutive years and pay a fine. After completing the two-year conditional period, workers would qualify for lawful permanent residency. The legislation covers workers in health care, energy, agriculture, emergency response, education, hospitality, construction, home health care and child care industries. Reps. Juan Vargas of California, Nydia Velazquez of New York, Delia Ramirez of Illinois and Angie Craig of Minnesota are co-sponsoring the bill. “Right now, Trump is implementing an out-of-control anti-immigrant crackdown,” Vargas said in a statement. “It’s past time to fix our broken immigration system and create better pathways to citizenship.” Business groups supporting the legislation argue that current immigration enforcement is creating labor shortages and reducing consumer spending. “The Strengthening Our Workforce Act adds to the growing bipartisan Congressional momentum to end the mass deportation efforts that are causing labor shortages,” said Frank Knapp Jr., managing director of the Secure Growth Initiative, which represents over 100,000 small businesses. The bill faces an uphill battle in Congress, where Republicans have generally opposed expanding pathways to legal status for undocumented immigrants. New Mexico will soon release rules for new bans of everyday products that use ‘forever chemicals’9/4/2025 State environment secretary plans to spend $2M to move people off wells in Curry County By DANIELLE PROKOP Courtesy of Source NM New Mexico will soon release an initial draft of rules to ban consumer products that contain so-called “forever chemicals,” the state’s top environment official told lawmakers Tuesday.

Earlier this year, Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham signed House Bill 212, passed by lawmakers to institute the gradual phasing out of intentionally added per-and-polyfluouroalkyl substances in everyday items. Lawmakers also passed a second bill, House Bill 140, to allow the New Mexico Environment Department to regulate and manage cleanup for firefighting foams containing PFAS on military bases, which have caused contamination in groundwater around the state. “Both of these laws work together to keep PFAS out of our economy, out of our drinking water and out of people’s bodies,” Environmental Secretary James Kenney told lawmakers during an interim Radioactive Materials and Hazardous Waste interim committee meeting. New Mexico is the third state to enshrine a ban in state laws to address the use of PFAS in consumer products, joining Maine and Minnesota. This class of manmade chemicals is often used in waterproofing and is able to withstand breaking down in water, oil and sunlight. As a result, PFAS can be found across a range of products, including cookware, takeout containers, dental floss, cleaning supplies, cosmetics, menstrual products, textiles and upholstered furniture. But exposure through contaminated water and soil, as well as through the plants and animals, cause PFAS to build up in the human body. While still being studied, PFAS exposure is linked to increased cancer risks, fertility issues, low birth weights or fetal development issues, hormonal imbalances and limiting vaccine effectiveness. The initial rules will be released sometime in September; require a public input process; and approval from the seven-member Environmental Improvement Board. Once approved —potentially next summer — the PFAS ban would roll out in phases, starting with cookware, food packaging, firefighting foams, dental floss and “juvenile products,” by January 2027. Additional items would follow, such as cosmetics, period hygiene products, textiles, carpeting, furniture and ski wax. The rules will include exceptions for PFAS used in products such as: medical devices, pharmaceuticals, electronics and cars. Kenney said the rules will contain instructions requiring manufacturers to label products containing PFAS; establish a process for companies to receive an exemption if needed; and develop fines for companies violating the ban. The department will also soon be releasing its draft rules on regulating firefighting foams containing PFAS, expected to receive final approval in the fall 2026. Those rules, Kenney said, will help environment officials develop a statewide inventory of the foams and determine how to characterize, treat and ultimately dispose of them. Kenney highlighted the recent report issued by the department finding the “fingerprint” of firefighting foam PFAS in people’s blood in Clovis, surrounding Cannon Air Force Base. As a result of those findings, Kenney said the department is working to spend $2 million lawmakers set aside in capital outlay to move people off of private wells and onto public drinking water systems. Furthermore, the department plans to conduct additional testing around Holloman Air Force Base and push for cleanup as multiple federal lawsuits between New Mexico and the military remain in the courts. “We are going to continue to be in a groundwater war and a public health war with the Department of Defense,” Kenney said. Sen. Ant Thorton (R-East Mountains) asked what the minimum level of exposure is safe for PFAS and what the state considered realistic. Kenney said that he couldn’t provide an exact number “since I’m not a toxicologist,” but instead compared PFAS contamination in drinking water systems in two locations with known exposure: Curry County, near the base, and La Cieneguilla, which has detected contamination from the Santa Fe Regional Airport. Curry County, he said, has higher risks of exposure, as its drinking water has PFAS levels 650,000% higher than federal standards. While “not negating” La Cieneguilla’s concerns, he said, levels for that community are “much closer” to the federal standard. “We need to figure out where the greatest risk is occurring and minimize it from there,” Kenney said. “I think many people would say there’s no acceptable risk level for PFAS, I’m a little bit more pragmatic — it’s a forever chemical. It’s going to be hard to get out of the environment, and our risk is always going to be something greater than zero.” And how do I make them stop? By Zach Hively Why do people talk to me? This isn’t entirely about the brothel next door (which I told you about last time). But it is also about the brothel next door. I had a perfectly good ignorance going until the neighbor piped up about my dogs and me scaring off the, erm, clientele. I had figured the many skulking men coming (and then promptly going) were friends, or plumbers giving estimates, or friends and plumbers buying fentanyl. I would never have known what was afoot (or abed) if she hadn’t seen fit to talk to me. My life generally runs more to my liking when people don’t do that. Or, if they must do that, when they stick to talking about the weather—hell, when they stick to talking about the Broncos. Instead, lately they choose, out of all the topics in the world, to talk at me about the Holocaust.

SOCIAL TIP #1: The Holocaust is not a natural progression of conversation with your customers at the post office. This happened when I was at a post office different than my home post office. I appreciate the people who work at my home post office. They sometimes let me use the MEDIA MAIL stamp on my packages. They talk to me about flowers and dragons made out of Legos. They have never once tried to persuade me that a historical atrocity was anything but. They are sticklers for rules at my home PO—so I’m pretty certain that discussing historical atrocities in a contemporary context is not USPS policy. The best part about going to the post office away from my home turf is that my stale material becomes fresh. Like when, in compliance with USPS policy, a USPS employee asks me if my package contains any hazardous or dangerous materials, despite my package containing only books. “Not under normal operating conditions!” I like to say. At which point my home postal officers hand me the MEDIA MAIL stamp to keep me occupied. I read the (very empty) room at this away-game post office and called an audible. Any dangerous or hazardous materials? “No more dangerous than a book!” I chirped. So what came next was sort of my fault, but not really. “Pretty dangerous, then!” said the woman—let’s call her “Dee” because she made sure I knew her name when she asked me to answer the survey about my experience. So far, so good. This was banter. “That’s why the N—zis burned them!” I mean, she was NOT WRONG, but still my biblio-senses were tingling, and not in the cozy-bookstore-on-a-rainy-day way. “You wanna know why they really burned books?” Dee said, clearly deciding mine was a face she should talk to. I did not, in fact, want to know. But she had me by my package, which I had relinquished but not yet paid for. “J—sh s—ual deviancy,” she said, only she did not censor or otherwise hush herself like I do for algorithmic purposes. And then she kept talking and I noped out on the inside but not on the outside because Dee got herself so riled up that she mis-stamped my package and had to work off the wrong label with what looked an awful lot like her personal nail file. She started my transaction over, including a reprise of the hazardous materials question. I’ve never played my answer so straight in my entire book-shipping life. And this was the second time that week that a stranger took one look at my face during an innocuous exchange and turned it into explaining why Everything I Know About History Is Wrong. The first was at an Argentine tango dance in an entirely different ZIP code than Dee. One of the trademarks of tango culture is the peculiar way we ask each other to dance—not with words, but with staring. This tradition makes tango the ideal social activity for those who don’t want strangers talking at me. Yet despite these codes of conduct, a woman I do not know sat with me and chatted on about an experience she’d had with a foreign dancer who related how staring lands differently in his culture. I believed it, I said—having lived in parts of Europe where grown adults can stare you down with impunity for an entire train ride from Barcelona to Berlin. I did not see this as any sort of invitation down any holes, rabbit or otherwise. But she leaned in and said—loudly, to be heard by half the dance floor over the music—“I was doing my own research, and you want to know who really won World War II?” SOCIAL TIP #2: DO NOT DO THIS, EVER. So I am finished with people for a good long while. Becoming a shut-in is the only way to avoid strangers who Do Their Own Research and think, for whatever reason, that I want to hear about it. If they really, really like reading into conclusions for themselves, then I suggest they start reading my face before opening theirs. |

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed