|

Just when we thought we’d seen everything, Congress has thrown down a breathtaking new gauntlet: a national work requirement for people participating in Medicaid. Every state will now be required to track the employment status of its Medicaid recipients in order to receive federal funding for the program.

We don’t know exactly how New Mexico will enact this new rule. The “One Big Beautiful Bill” does not prescribe how to set up such a tracking system, and it certainly doesn’t fund it. But every U.S. state will need the system in place in extremely short order, most likely by late 2026. There are a lot of unknowns, but what we do know is this: Work requirements don’t work for people with disabilities. As CEO of Disability Rights New Mexico, I have seen how every year, we provide free legal services to thousands of people with disabilities across our state. We exist, in part, because the systems designed to support people with disabilities are so often unnavigable. Now, Medicaid will erect a new barrier that many people with disabilities won’t be able to scale. The new legislation requires that Medicaid recipients prove that they work, volunteer or attend school for 80 hours each month as a demonstration of worthiness for coverage. If people fail to report, their health care is cut off. There may be some exceptions to the work requirement for folks with medical issues or parenting obligations. But whether or not they are required to work, we are profoundly uneasy about the ability of many people to navigate a reporting system that requires regular check-ins and submission of documentation. Even if someone is entitled to a medical exemption, they don’t necessarily have the ability to provide regular proof of it. Consider the following common scenarios: A young man with an intellectual disability works in a warehouse, where the predictable routine and structure support his ability to succeed on the job. He is enrolled in Turquoise Care, New Mexico’s basic Medicaid plan. Despite working 80 hours each month, his disability makes it impossible for him to regularly report his work hours to the state. Even though he is meeting the requirements, he loses his health coverage simply because he cannot navigate the reporting system. A woman with traumatic brain injury meets the medical criteria exempting her from work. However, her disability deeply impacts her executive functioning skills to the point where she is incapable of filling out the exemption forms, scheduling a medical appointment to certify her status and regularly submitting the required documentation. Because of impairments caused by her disability, she loses her health care. These aren’t hypotheticals. These are real examples of the many disability-related obstacles faced by real New Mexicans. And a lot more people are about to be impacted. According to New Mexico’s Health Care Authority, HCA, New Mexico has 836,000 enrolled in Medicaid, approximately 40% of New Mexico’s population. Approximately 254,000 Medicaid members would be subject to the bill’s new work requirements. Although the details of exemption requirements have not been disclosed, we can expect a significant number of this group could lose coverage, not because they are unwilling to work, but because the policy ignores real world barriers. HCA estimates that nearly 89,000 will lose coverage for vital health care. We expect that number could be significantly higher, particularly in the rural areas where work and volunteer opportunities are limited. Added to that reality is the limitation of transportation of essential transportation services. As if those were not enough barriers to overcome, there is the new six-month redetermination requirements that pose an additional threat to maintaining continuing eligibility, especially for those with disabilities attempting to continue to meet paperwork requirements. They will be subject to a confusing and punitive federal reporting mandate. These individuals will need ongoing support to navigate the new rules and how to follow them. We shared these concerns with U.S. Rep. Gabe Vasquez (D-N.M.) at a recent Medicaid roundtable, and he has taken action to try and right the ship on Medicaid. The entire Congressional delegation has been supportive of New Mexicans regarding the consequences of these Medicaid changes. We ask that other state New Mexico lawmakers and state leaders do the same, recognizing the chaos and harm that will be unleashed by this new federal mandate and taking steps to do something about it. We call upon our state’s leaders to develop, fund and support an employment reporting system that is as accessible, inclusive and fair as possible. We cannot allow the Medicaid system to punish the very individuals it was established to support by depriving them of essential health care services.

0 Comments

Ahead of Social Security’s 90th anniversary next week, U.S. Rep. Melanie Stansbury (D-N.M.) said during a news conference in Albuquerque on Thursday that actions taken against the social safety net program by the so-called Department of Government Efficiency are laying the groundwork for its privatization.

“Part of what we’ve seen since DOGE has taken over Social Security is that they’ve dramatically cut back hours, they’re trying to shut down centers all over New Mexico, including in Rio Rancho,” she said. There are 468,030 New Mexicans who receive monthly Social Security benefits, including retirees, disabled workers and children, according to a news release from Stansbury’s office. Albuquerque has one of the largest Social Security call centers in the country, Stansbury said, which serves beneficiaries across the nation. The staff there told her office during a recent visit that the facility was built to house as many as 500 workers, and is now down to approximately 200, she said. “DOGE has hacked into the computer systems and data of the Social Security system,” she said. “The system is crashing.” John “JD” Doran, an American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees retiree and second vice president of the NM Alliance for Retired Americans, said people using Social Security to survive are experiencing longer wait times, broken websites and delayed claims. “You have no idea what retirement security means until you retire and find out you don’t have it,” Doran said. “We’re trying to prevent that from happening. Social Security contributes more than $3 million to New Mexico’s economy every month — that’s what keeps this state strong.” Stansbury last month introduced the Hands Off Our Social Security Act, which would make it illegal for any federal administration to privatize Social Security; require Congressional consent to downsize the Social Security Administration’s workforce and offices; mandate that the program maintain public access via phone lines; and protect beneficiaries’ sensitive personal data. Stansbury said the bill was prompted by the DOGE Subcommittee’s last hearing in which a panel of conservative analysts with the Heritage Foundation and associated organizations discussed privatizing the program. Stansbury is the committee’s ranking Democratic member. When Stansbury introduced the legislation, she said on the floor of the House of Representatives that the Trump administration “is trying to systemically dismantle” Social Security. More than 70 million Americans rely on Social Security, co-sponsor U.S. Rep. John Larson told the House. He said it is the country’s “number one anti-poverty program” for seniors and children, and more veterans rely on it than the Veterans Administration. Stansbury said on Thursday Larson told her the GOP and think tanks in favor of privatization’s end goal is to break the Social Security system now so that they can make the case for privatizing it later. “They don’t want it to work,” she said. “Really big money is behind being able to take the principal that you paid into Social Security your entire life that you worked, and they want to take that money and gamble it on the stock market so that they can make money off of it.” Stansbury said she doesn’t think it’s likely the current Congress will take up her bill because it is “trying to dismantle so many of these programs.” “But we felt it was important to take a strong stand and say: ‘Do not privatize Social Security,’” she said. “We’re going to fight back with everything that we can.” State’s new broadband boss says satellite is ‘significant’ in getting New Mexico 100% connected8/14/2025  A plow lays fiber directly behind it in the Ramah Chapter of the Navajo Nation in an undated photo. While the state has invested heavily in fiber for internet connectivity, the state’s broadband office director said told a legislative committee Monday that satellite internet could be a “significant” part of the puzzle as it seeks 100% connectivity. (Photo courtesy Jeff Lopez’s legislative presentation) Even with federal changes to a huge funding stream for New Mexico, 90% of the state has access to high-speed internet, and contracts will be in place for the last 10% by the end of next year, the new leader of a state broadband office said Monday.

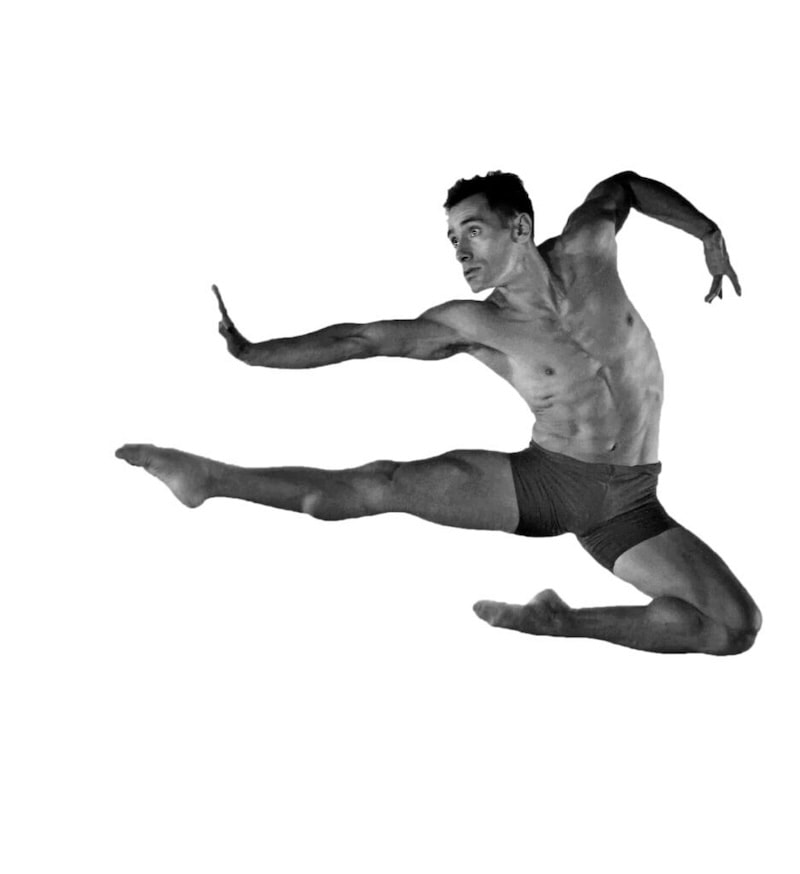

And to get over the finish line, satellite internet is a “significant part of the picture,” said Jeff Lopez, who is beginning his eighth week in charge of the New Mexico Broadband Access and Expansion Office. Lopez was speaking to state lawmakers on the interim Economic and Rural Development committee. “We are still ‘fiber first,” Lopez said. “We’re focusing on areas that are financially prudent for that fiber connectivity, but low-Earth orbit satellites are going to be part of the picture, again, of meeting that commitment by the end of 2026.” Roughly 90,000 New Mexico locations are “unserved” or “underserved” in terms of broadband access, according to Lopez’s presentation. “Unserved” households have download speeds of less than 25 megabits a second, while “underserved” have download speeds between 25 megabits a second and 100 megabits a second. A household of four with a 100-megabit download speed could stream videos, work remotely and have video calls like for telemedicine, “but not necessarily all at once,” Lopez said. The extent to which New Mexico’s internet connectivity plans include satellite, has been an open question amid federal changes to an infrastructure spending bill passed during President Joe Biden’s term.Also, during the legislative session earlier this year, as Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency was firing federal workers and dismantling federal programs, state lawmakers removed $70 million for satellite internet in the state budget that the previous broadband director said would likely have gone directly to Musk’s company satellite internet company Starlink. That funding cut does not affect the office’s timeline. Satellite internet companies can provide access in rural areas and those where overlapping jurisdictions or topographical features make it difficult and expensive to bury fiber lines Lopez said. But he also said fiber is “future proof” because it’s a largely permanent installation safely underground “We still believe that [fiber] is the best connectivity that money can buy, but it’s often much more expensive than alternatives,” he said. Satellite, on the other hand, is not as resilient to natural disasters, he said, and the technology isn’t “fully fleshed out yet.” “It makes sense in areas with open skies, but we also have a lot of communities along waterways and valleys, along bosques, whether it’s tree coverage or just a mesa or a mountain in the way, that can also impede some of the access,” he said. Biden’s infrastructure bill created the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment Program to oversee billions of dollars in internet connectivity spending. The state broadband office successfully qualified for $675 million of it and, Lopez said, was in the final steps last month of awarding sub-grantees the funding. But in early June, the National Telecommunications and Information Administration announced rule changes to the program that leaders said were aimed at reducing regulatory burdens and ensuring that all broadband technologies had equal footing when competing for the funds. The change toward “technology neutrality” meant the removal of “previous restrictions that favored fiber deployments,” according to a news release from the broadband office in early July. In addition to giving satellite a better shot at the funding, the rule change required all potential recipients of the funding to submit a new round of applications “regardless of where the state was in its sub-grantee selection process,” according to the news release. Two satellite companies have put in bids for the federal broadband funding, Lopez said Monday. He declined to name which companies are seeking the funding. “But you might be able to guess,” Lopez told lawmakers. According to the state Broadband Office’s application page for the federal money, SpaceX, which provides Starlink, is one of a handful of “prequalified applicants” awarded that status after the recent rule change.* Another satellite provider previously “prequalified” is Amazon Kuiper, according to the office’s website. *Correction Aug. 12 at 10:03 a.m.: This story has been updated to correctly reflect that Amazon Kuiper, another satellite internet provider, is also on the list of “prequalified” applicants, along with SpaceX’s Starlink. Roger Montoya believes teaching dance helps students gain lifelong skills centered in the creative development of the mind, body, and spirit. His organization, Moving Arts Española, serves the rural communities that make up his native northern New Mexico—areas hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis and where a large percentage of residents live in poverty. Through its facility located in the town of Española, Moving Arts offers classes spanning arts disciplines including dance, music, painting, gymnastics, sewing, and cooking, plus internships, community engagement, and, above all, personal investment in the success of the students. “Mentorship is masterful,” Montoya says. “It’s an age-old tradition of honoring the craft and instilling discipline, and then allowing a young person to find their own way within that choreography, pun intended.” At Moving Arts, Montoya is creating a unique space of healing and hope. “My philosophy is really that art is medicine,” he says. Montoya began dancing at age 20, after growing up drawing and painting and training as a gymnast during his adolescence. He studied at The Ailey School, the Martha Graham School, and with a variety of other influential companies and artists in New York City before joining the Paul Taylor Dance Company as an apprentice and, later, becoming a company member at Parsons Dance. In the mid-1980s, after learning he had HIV, Montoya ended his stage career and returned home to spend what he believed would be his final years with his family. Instead, he found a calling. “The juxtaposition of the opulence, excitement, and opportunities of New York City against the rural, underserved landscape of New Mexico—and the talent of the young people around me [who had] no access to the things I had enjoyed as a 29-year-old—it felt like a great opportunity to open those doors for young people in this region,” he says. In 2008, Montoya officially co-founded Moving Arts with his partner, Salvador Ruiz Esquivel—after spending nearly two decades unintentionally laying the groundwork. With no formal background in education, Montoya began by offering gymnastics classes in the community from 1990 to 1995. Those classes led to a district-wide in-school arts program for 3,000 students in kindergarten through sixth grade. An after-school program followed, which finally led to Moving Arts in its current iteration. Moving Arts has continued to expand over the years, and, in 2012, was authorized by the State of New Mexico to create a (now-shuttered) public K–8 charter school of the arts and sciences that served as a feeder program for the prestigious New Mexico School for the Arts. The lasting impact of Montoya’s own mentors also inspired his work in the Española community. He cites former Limón Dance Company principal Louis Falco and dancer and choreographer Mary Jane Eisenberg, as well as his first art teacher and his high school gymnastics coach, as important guiding lights in his life and career. “I was really struggling, and [my first art teacher] saw my gifts as a painter and visual artist,” Montoya says. “She provided that first moment of knowing ‘I am safe, I am honored, because this person sees me.’ ” He hopes each child who passes through Moving Arts’ doors experiences this same sense of safety and belonging. “I truly don’t know where I would be had I not got involved with Moving Arts and not been supported to try a new thing, which was dance,” says Than Povi Martinez, a Moving Arts alum, dance artist, and 15-year mentee of Montoya’s who recently graduated from Loyola Marymount University’s dance program. “Roger has always been there and has always offered a hand of support and words of encouragement.” Montoya is currently creative director of Moving Arts. His roles include strategic program development and grant-writing, as well as teaching ballet and modern dance classes, teaching visual arts, choreographing, and overseeing set production, costume, and prop design for performances. He and Ruiz Esquivel also mentor students directly or connect them with one of the 35 multidisciplinary working artists affiliated with Moving Arts.

After receiving a 2019 CNN Heroes Award, Montoya had been encouraged to run for office by members of the New Mexico federal delegation—as well as his mother, Dorotea Montoya, who was a respected figure in the health-care community and another of his key mentors. He served one two-year term, during which he was an advocate for New Mexico’s rural communities, focusing on issues relating to health and human services, infrastructure investment, and justice reform via committee work in courts and corrections. However, Montoya says his time in politics ultimately led him back to his core belief that working in the community—and making change from the ground up—would give him the opportunity to make the biggest difference.

“The most impactful moments in my career have been when a young person finds his or her place in art-making,” Montoya says. “In order to make lasting change, we have to cultivate a new generation.” Ryan Dominguez shares memories of his mother. By Jessica Rath When I do interviews for the Abiquiú News, I’m frequently impressed and touched by what I learn about the person I’m talking to. Especially when it comes to people I’ve casually known for ages, I’m awed by the complexity I discover: the individual becomes multi-dimensional when they tell me about their past, their interests, their life journey. A case in point was Ryan Dominguez who I first met some twenty years ago; he and his wife Jeanette were neighbors, plus we were members of the Abiquiú Volunteer Fire Department. But I had no idea that he was a performing guitar player and a music teacher until I interviewed him. And how did he get into music and playing the guitar? His mother encouraged him. There was nothing to do for a young kid in Abiquiú, but when he complained about being bored, his mother told him to pick up the guitar that was in the house, and learn how to play. “Being bored” was not tolerated. Ryan kindly agreed to share some more stories about his wise mother. Her name was Criselda Dominguez, born and raised in Abiquiú, and she had twelve children. You’d think this was enough work, but she found the time for an enormous amount of volunteer work, benefiting the Abiquiú community. She also had a regular job, she worked for Ghost Ranch, but this wasn’t a “normal” nine-to-five job either, Ryan told me. “She worked at all hours. Her job consisted of taking the elderly to any appointments that they needed. If they needed groceries, she would take them. She would do their income tax for free. She also did a lot of volunteer work; she probably volunteered for every board there was here in Abiquiú: the library, the gym, the recreation center. At one point she did work for Georgia O'Keeffe.” “My Mom would try to bring helpful programs for the people here in Abiquiú,” Ryan went on. “In the summertime, she'd open the gymnasium next to the church, so that the kids would have a place to be during the summer when school was closed. It was almost like a daycare, people would drop their kids off, and they would stay there the whole day. My Mom noticed that the kids weren't leaving for lunch because they were simply dropped off. She just couldn’t let the kids go hungry, so she went to the county to see if there was something that they could do about feeding the kids. They actually developed a summer meal program: they would bring lunches and drinks for the kids at the recreation center, so that they would have something to eat.” “That’s what my Mother did in the summer. She was also part of Save the Children, an international charity organization similar to UNICEF. She would go around Abiquiú and take pictures of kids that were experiencing hardships and then submit the paperwork, and they would get sponsorships from people outside of New Mexico. The type of sponsorship the kids would receive was clothing, school supplies, or just extra cash to help out.” Ryan’s mother was primarily concerned about children and the elderly. She did this during the summer for at least 20 years, I learned. “She also brought a Senior program to Abiquiú, where they would feed the Seniors,” Ryan continued. “That way, they had a place to hang out at the parish hall, and they could visit with each other. She was always looking out for how she could help the people from Abiquiú.” “She would also help with the commodities: free food from the government, such as cheese, milk, fruits and vegetables. They sent it to her house and we would get all the boxes ready, and then my mom would call people to let them know that they could pick it up from her house. This happened only once a month, and she wanted to do more for the community. She ran a food program where people could get $30 of groceries for only $15, for half the price. It wasn't a nine-to-five thing, more like eight-to-ten. It didn't matter when they needed something, my Mom never turned anyone away. She would never say, ‘come back tomorrow.’ She would never say anything like that. If people needed something, she was always there to help.” Sometime in the 1980s Criselda won the New Mexico Woman of the Year award for all she did. It was an acknowledgement for all she did for the community, and she was invited to have a meal with the governor. Plus, it was featured in the news.

Ryan told me: “I remember another story: on Sundays, after mass, she would go visit the elderly, and while she was visiting, I had to chop wood and stack it for the whole week. So, while she was inside visiting, I was outside chopping and stacking wood. We’d go from one house to the next and I couldn't receive any payment. I had to volunteer my time. Although they wanted to give me money, I was not allowed to accept it. My Mom had prearranged that I would not receive any money.” “Then, in 1983, our family home burned down. The community came together and rebuilt my Mom's house in about two weeks because of all that she had done for her neighbors and other people in the village. She cooked for everybody, that's all she could afford. When you have a job and you have twelve kids, clearly you don't have any money to spare. She gave in so many other ways. For example, my Mom started collecting clothing. If people from other countries came and they didn't have any clothing, they would just go to my Mom's house and would pick out whatever they wanted. She never took any payment because she really lived a selfless life.” I wondered – was she very religious? Was that maybe part of the reason why Criselda was so selfless, because she believed that when she was helping others she was serving God, and that's the way humans should behave? Ryan affirmed my question: “Yes, my Mom was very religious and what mattered to her was not so much what you receive in life, but what you can give someone else less fortunate. When I would complain about our lifestyle, because we were pretty poor, she used to tell me that we were blessed, because there were others even less fortunate than us.” “When I was younger I couldn't understand this. I wore torn jeans with patches on them. My Mom would sew some of our clothes, and so I was always wearing some hand-me-downs, almost everything was a hand-me-down. And I couldn't understand why. As I got older, I could finally understand that. And, today, when I see that the fashion nowadays is to wear torn jeans, I have to laugh that people are paying for them. I joke with them, and I tell them: ‘You know what? I initiated that style!’ Now that I'm older I totally understand that my Mother did what she could with what she had. And she even gave more without any expectation for payment.” So many people nowadays seem rather selfish, they only think about what's good for them and never consider anybody else. I find that rather sad. It might have been hard for Ryan to grow up with torn jeans and hand-me-downs, but I'm sure that now he feels very appreciative for the way he was brought up. Maybe you feel kind of blessed to have had those experiences, I asked Ryan. “Yes, I am appreciative,” he answered. “My Mom always looked at things like the glass is half full. Back in the day people had to dig their acequias. And the elderly would call my mom and ask, ‘Do you have any sons that can do the acequia for us?’ Sure enough, my Mom would say, ‘How many do you need?’, and then she would line us up and tell us, ‘You're going’, ‘You are going’, and ‘You're going’. We had no choice. We would have to go and do the acequias. And after a weekend of working on an acequia, which wasn’t easy work, I would get a paycheck: they would pay us $25. $25 for 24 hours of work. I remember saying to my Mom, ‘This is not worth it. $25 for 24 hours of work is not worth it.’ But she would tell me, ‘Well, that's $25 more that you have now than you did on Friday, right?’ This taught us the value of hard work.” I think it's good to be reminded that there are so many people who have so much less and who are suffering much more. We often feel unhappy because we can’t afford the next shiny thing, while overlooking that we actually have enough, all we need and more. That we have so much to be grateful for. Ryan confirmed this. “We were always taught to be thankful for what we have and to consider that we were blessed, because we did have the necessities. They weren't the best necessities, but there were enough, all we needed”. Criselda passed away when she was 77 but until then and after she retired from Ghost Ranch, she continued to volunteer for many different organizations. She served as a board member for Las Clinicas Del Norte, and she served on many other boards in Northern New Mexico. She always had to be involved with something, Ryan recounted. Towards the end of her career, when her children started to move out, she found a way to surround herself with kids, because all throughout her life she had been around children. She decided to volunteer as a grandma at the elementary school, she enjoyed the presence of children so much. “It was interesting, she called everybody my dear,” Ryan continued. “Like, ‘Hi, my dear’, or ‘How are you, my dear’. And that’s why she became known as La Dear, because she said it to everyone. There was a type of respect that you don't find much anymore. My Mom was stern, but she was not mean. She asked you to do what was expected of you. I remember when I would receive awards at school, she never told me that I was doing a good job, she never praised me. Her understanding was, if you do something at 100% the way you're supposed to, why should you expect awards? You don't need any compliments for that because you're just doing what you're supposed to do.” That must have been a little hard sometimes, I would imagine. “Yes, it was,” was Ryan’s reply. “But I now understand that you shouldn’t expect praise for what you should be doing, right? If you're living right, that's what you're supposed to be doing. Don't expect praise for something that is expected of you. It was sometimes hard for us kids to understand, but she would show her love and gratitude towards us through facial expressions. I was never allowed to complain. My Mom believed that if you feel blessed, then you shouldn't complain. You should be grateful. That was her stance in life. If you're not part of the solution, then you're part of the problem.” There is a lot of wisdom in Criselda’s way of bringing up her children. She taught them never to play the victim but that they could be whatever they wanted, that they will reach their goal with hard work. Ryan said: “She taught us, don't expect to be given anything. If you expect something, you're going to be disappointed when it doesn’t happen. But if you don't expect anything and then you get something, you'll be happy.” Criselda passed away in 2010 and she was helping people, volunteering till her last day, Ryan told me. She was diagnosed with stage four cancer, and she lived for almost a month after she learned of her illness. Not once did he hear her complain, although she must have been in agony – the cancer had spread to her bones. “That's the way she was: regardless of all the pain that she was in, she never mentioned it.” Thank you, Ryan, for sharing your memories about your mother with us. I will think of her the next time I want to complain about the heat, or if I feel sorry for myself because I can’t afford the cute-looking shoes that I don’t really need. And I will remember to cultivate a sense of gratitude for everything that supports me. What a great teacher your Mom is. It's my desert-iversary. By Zach Hively This week marks the anniversary of my return to New Mexico, where I was born and where I grew as tall as I’d ever get—where I didn’t appreciate my surroundings until I left and came back and left again and came back again—where I needed to return to settle into myself. It’s the same week when I moved into the house I’d been fixing up for a summer. I needed New Mexico again, but I didn’t want the city this time. I wanted mountains with nearly nothing between me and them but crows and smoke from someone’s brush burn. I wanted space to think and breathe and maybe sometimes disappear, for a while. I found a space to write more poetry than I ever had. These poems are some of the ones that came out in this headspace and heartset. They are from a suite called “Five Times Coming Home." Other People They worry about me being here as clear as snake tracks in the sand. As if I will tire of reading worn stones and could ever translate the strata of stories in the walls sheered by guerilla floods and illuminated by the roots of cedars, patient monks. As if I could ever smell over the next ridge to my satisfaction and finish tallying the stars on my walls like the count of my days. As if I need more than myself and the indifferent welcome of this, my companion land. Untaming feral mind, feral heart rocks dirt trees fire and sky, moon and sun the flow and ebb turning toward, drawing away where is the wild man the shapeshifter with smoke and stories has he forgotten himself here no mistakes more serious than joy reacquainted with feet and hands find the sky again grow thick with quiet continue choosing turning toward to feel it all all ways of being are not exclusive lay them bare again and always Querencia

My way is not the only way. I must learn from other ways to test and hone my ways, to make way for those other ways any way I can. There is no right way to love this place or let it love me back, to test and hone me and stun me with an evening flower or a print in the snow, to make way for others as others made way for me. Submitted by Representative Kathleen Cates (D-Rio Rancho)

New Mexico’s arid climate means we naturally receive limited annual precipitation, but the effects of climate change have exacerbated these challenges. Rising temperatures have led to prolonged droughts, decreased snowpack, early melting, and reduced river flows, while higher evaporation rates have diminished our water storage in reservoirs. To secure our water future and protect our agricultural communities, we must address these issues alongside a complex tapestry of cultural and economic factors. Decades of underinvestment in aging infrastructure also impact the state’s ability to send water to the communities that need it. The El Vado Dam and Corrales Siphon, for instance, are no longer functional, severely hurting nearby farmers. Similarly, utilities are struggling to fund the maintenance necessary to keep our drinking water safe. Over the years, water usage has shifted dramatically toward urban consumption, energy production, and large-scale agriculture. Over-reliance on groundwater extraction has led to the depletion of many of New Mexico’s aquifers. In some areas, water tables have dropped so significantly that wells have run dry, leaving communities and farms without a reliable water source. Small family farms in particular have suffered as decreased water supply lowers yields, causing some farmers to lose agricultural status on their taxes. This has cost many already-struggling families their traditional livelihoods. To preserve New Mexico’s farming communities, we must take action to improve irrigation, provide financial support, and strengthen traditional community entities, such as acequias. Our state legislature has funded hundreds of water projects across New Mexico and made it easier to get funding through the New Mexico Finance Authority’s (NMFA) Water Project Fund, an important win for farmers and rural communities. We also adopted the Strategic Water Supply Act to address scarcity by funding the treatment of brackish, previously unusable water from deep aquifers, helping to increase water availability to farmers as well as the manufacturing industry in our state. Still, these efforts alone are not enough to address overconsumption. We must also reduce nonfunctional water use, such as the watering of non-native ornamental turf (grass), on land other than schools, parks, and athletic fields, which consumes significant amounts of our limited water resources. To lead by example, I sponsored a bill this past session that would require the state to use low-water-use landscaping when installing new groundcover and replace current grass areas over a number of years. Another major contributor to overconsumption is illegal water diversions. Current state law gives us little recourse to address water theft, with industries paying nominal fines for overuse without ever adjusting their consumption. We may need to strengthen penalties to help better enforce these laws. As the legislature increases funding and support for students pursuing trade careers, roles like water controllers, managers, and engineers must be part of this investment. I can think of no more important, mission-driven occupation than delivering clean, safe water to your community. In the coming legislative session and beyond, we will prioritize providing support to our farming communities and reducing our overall consumption through wastewater recycling, targeting water theft, and reducing unnecessary usage of water. Addressing this crisis will require unprecedented investments from the state and federal government to keep water flowing to the farmers that need it and to keep safe drinking water accessible in every corner of New Mexico. Cates represents parts of Northwest Albuquerque, Corrales and Rio Rancho Sen. Heinrich leads fight to halt federal job cuts threatening New Mexico’s $9 billion lab economy8/6/2025 New Mexico’s senior senator is leading national legislation to halt federal workforce cuts that threaten thousands of jobs at Los Alamos and Sandia national laboratories, which pump nearly $9 billion into the state’s economy annually and employ about 30,000 New Mexicans.

U.S. Sen. Martin Heinrich, ranking member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, introduced legislation Tuesday with fellow Democrats to impose an immediate moratorium on Reductions in Force (RIFs) at the Department of Energy, U.S. Forest Service, and Department of the Interior — three agencies with massive New Mexico footprints. The move comes as the Trump administration and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) have already eliminated significant portions of the federal workforce through forced resignations, early retirements, and a program paying employees not to work. “These agencies provide critical services that protect American public health and safety, conserve our natural resources, and advance America’s scientific leadership on the world stage,” Heinrich said in a press release. “Firing our scientists, engineers and land management professionals does not save us money—it makes our government less efficient, costs taxpayers more in the long run, and weakens our nation’s security and competitiveness.” Heinrich emphasized the laboratories’ economic importance during recent Senate hearings, noting their “combined economic impact on the state reached nearly $9 billion” in 2023. However, Energy Secretary Chris Wright assured New Mexicans in February that federal layoffs would have “likely zero impact” on the national laboratories, though he acknowledged broader Department of Energy cuts were underway. The agencies covered by Heinrich’s legislation have already experienced substantial job losses, according to multiple reports and federal officials. The U.S. Forest Service dismissed about 3,400 employees, approximately 10 percent of its workforce. In New Mexico, reports indicate that around 30% of the Santa Fe National Forest’s workforce was terminated, with Carson National Forest also seeing major cuts. The Department of the Interior fired about 2,300 probationary employees, including 1,000 from the National Park Service and 800 from the Bureau of Land Management. Heinrich reports that “as much as 20% of the National Park Service workforce at Carlsbad Caverns has been axed,” with cuts also affecting White Sands National Park, El Malpais National Monument, Bandelier, Valles Caldera and Gila Cliff Dwellings. The Department of Government Efficiency was created by Trump executive order on January 20, 2025, initially led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy. Despite its name, DOGE is not an official federal agency requiring congressional approval, but operates as an advisory organization tasked with eliminating “waste, fraud and abuse.” Musk left his DOGE role in May 2025, with Amy Gleason now serving as acting administrator of what the administration calls a temporary organization set to terminate July 4, 2026. The workforce reductions have occurred through several mechanisms: Reductions in Force (RIFs): Formal federal layoff procedures governed by Title 5 regulations for situations involving reorganization, lack of work, or budget shortages. Deferred Resignation Program (DRP): A voluntary program allowing employees to resign while continuing to receive pay through administrative leave, typically until September 30. At least 75,000 federal employees have taken deferred resignation packages, while thousands of probationary employees — those with less than one year of service — have been terminated. The Trump administration and congressional Republicans have defended the workforce reductions. White House spokesperson Harrison Fields called a July 2025 Supreme Court ruling allowing RIFs to proceed “another definitive victory for the President,” criticizing “leftist judges who are trying to prevent the President from achieving government efficiency.” The Supreme Court ruled 8-1 to allow mass RIFs to proceed, with only Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson dissenting, calling the administration’s actions “legally dubious.” Heinrich expressed particular concern about the timing of cuts to wildland firefighters ahead of fire season. “Lord knows we’re going to have a hell of a fire season this year,” Heinrich told The Santa Fe New Mexican. “That’s just insane. Why anyone would think that’s appropriate is shocking to me.” The Forest Service’s Southwestern Region, headquartered in Albuquerque, oversees eleven national forests across New Mexico and Arizona. The agency manages critical wildfire prevention and response across millions of acres of state public lands. The legislation faces an uphill battle in a Republican-controlled Congress that has generally supported Trump’s workforce reduction efforts. However, Heinrich and his Democratic colleagues argue the cuts threaten essential services that protect public safety and economic competitiveness. The bills would need to pass both chambers of Congress and survive a likely presidential veto to become law, making them largely symbolic unless Republicans break ranks to support federal workforce protections. By Jarred Conley

Over the past several weeks, I’ve been vocal about my concerns regarding the decision by the Santa Fe National Forest to “manage” a naturally started fire that began with a lightning strike in late June. Rather than allowing it to burn naturally within a controlled area or suppressing it once it was clear the fire was moving toward structures, livestock, or heavy fuel loads, they chose to actively expand the fire by igniting an additional 13,000 acres by hand and air. This was done under the claim that it would help create a resilient ecosystem and prevent future catastrophic wildfires. Ironic, isn’t it? The result is the 17,500-acre Laguna Fire. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. This was never the right time to light a fire of that size. Late June is historically one of the hottest, driest times of the year in northern New Mexico. The risk was known. The weather patterns are predictable. Snowpack and fuel moisture levels were already pointing to high fire danger. On February 18, 2025, the Santa Fe National Forest Service issued a public notice stating that it would not move forward with any prescribed burns in the spring. The decision was attributed to “current weather conditions” and a shift in focus toward preparing for the upcoming fire season. The message was made clear and visible. It was released in all capital letters, headlined PUBLIC HEALTH AND SAFETY UPDATE, and paired with a large “Prescribed Fire UPDATE” graphic. This type of announcement suggests that, as early as February, the Santa Fe National Forest Service recognized the landscape might already have been too dry or unstable to safely conduct prescribed or controlled burns or “managed” fires. It also points to the possibility that the agency anticipated a difficult fire season ahead. The timing of the post, issued in February rather than in April or May, underscores how early those concerns may have emerged. "PUBLIC HEALTH AND SAFETY UPDATE: Due to current weather conditions, the Santa Fe National Forest will not implement any prescribed fire this spring. Instead, the forest will focus on preparing resources for the upcoming fire season." — Santa Fe National Forest, February 18, 2025 A decision to cancel all spring fire activity is not typically made without some level of data and forecasting. The Santa Fe National Forest Service has access to decades of historical fire behavior, live fuel moisture readings, satellite imagery, and predictive models. When an entire prescribed fire season is called off before winter is even over, it raises the possibility that multiple indicators were already pointing to elevated risk. While the public may not know the full scope of the internal analysis that led to the February 18 announcement, the nature and timing of the message suggest the concerns were significant. That context is what makes subsequent actions difficult to understand. If conditions in February were concerning enough to halt all prescribed fire, it is reasonable to ask why the Santa Fe National Forest Service later moved forward with igniting 13,000 acres in late June. The same conditions that prompted the February decision may have still been present or even worsened. The February 18 post remains a public record that reflects an awareness of risk. If circumstances changed between February and June, the public has not yet been shown how those new conditions justified such a significant shift in strategy. My issue is not with the firefighters or independent contractors who worked to contain the fire. I’m grateful for the men and women on the ground who did everything they could, and I know my sentiments are shared within the community. My frustration is with the decision makers at the Santa Fe National Forest who signed off on this ignition and continued to call it a “managed fire” even after it was no longer within control. Using a natural lightning strike as a reason to then ignite thousands of additional acres by hand and air is not transparency. It’s manipulation. That’s not a natural fire. That’s a decision. The burn took place around the La Presa Drainage, a critical component of the Rio Chama Watershed. This area should have been protected from the start, not after the fire escaped. It wasn’t until Southwest Area Incident Management Team 1 took over, under the leadership of Operations Section Chief Jayson Coil, that the drainage finally got the attention it needed. Prior to that, there was no indication that its significance was being acknowledged or protected. The impacts of this fire are widespread. Ranchers lost livestock, and still continue to do so. Grazing allotments have mostly been reduced to ash. Wildlife, including elk calves and deer fawns, were caught during their most vulnerable season. Smoke settled into the valleys for days, worsening health issues for people who had no way to escape the air or cool their homes with air conditioning. Some families were stuck indoors during the hottest part of the year. Water used to fight the fire was pulled from the Rio Chama and Abiquiu Lake at a time when farmers in the Abiquiu Valley were already under water curtailment. Tourism has taken a hit. Outdoor recreation was shut down. And the insurance consequences are just beginning. Classifying this as a wildfire instead of a fuels treatment opens the door for cancellations and premium increases, with long-term effects on our local economy. Carson National Forest has conducted prescribed/controlled burns with far more caution, using seasonally appropriate timing and scale. They’ve shown that not every fuels treatment needs to become a runaway disaster. Mechanical thinning also remains a proven tool. It can reduce fuel loads without smoke, without destroying watersheds, and without putting firefighting resources in the wrong place at the wrong time. It’s effective and deserves far more investment and attention than it currently receives. The public deserves answers. What did this ignition cost? Where is the burn plan? Was NEPA followed? Were watershed protections built into the planning? If this was about forest health, it should have been done when the timing was right, not for convenience, not to avoid spending local budget funds, and not at the expense of public land and public trust. Providing the public with a link to a several hundred or thousand-page plan is not acceptable. These are government employees. They should be held accountable and made to show clear, easy-to-understand information. If there’s a loophole allowing the Santa Fe National Forest to burn at this scale without consequence, costing taxpayers more than five billion dollars in just three and a half years, it needs to be closed. This wasn’t stewardship. It was carelessness. The Santa Fe National Forest has consistently posted biased photos and narratives to defend their actions, while ranchers and residents have shared photos showing the devastation left behind. The consequences—financial, ecological, and human—are ones we’ll be dealing with for a long time. By Karima Alavi All photos by Karima Alavi unless indicated otherwise

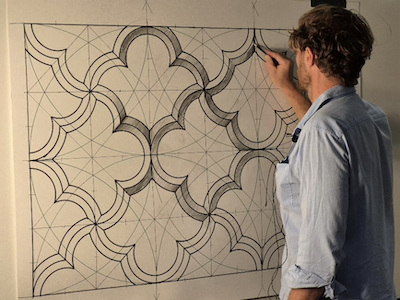

That could have been a new one for artists who attended the recent four-day workshop on the Art of Sacred Pattern. Yet Ari Lacenski of Portland, Oregon, the first attendee I encountered when visiting the workshop, was quick to assure me that the yellow powder she was using was most assuredly not gamboge. I was impressed; she was clearly familiar with one of my favorite books, Color, A Natural History of the Palette by Victoria Findlay. Ari was impressed that I was impressed. Few people are familiar with that little jewel of a book. Our conversation swept across the dangers of some natural pigments before moving to the piece she was working on in a quiet spot of shade she’d discovered. During the program I met faculty from as far away as London, and participants who drove or flew in from a variety of states. Some were in Abiquiu for their first time, some were drawn back to Dar al Islam after enjoying an earlier onsite experience with this event. However, one participant from Somerville, Tennessee, mentioned he had taken these courses online during Covid. He was thrilled to attend the event in person for the first time last year, an experience made special by the fact that he finally met some faculty and participants he had only known before as “zoom faces.” Like many of us, he considers personal connection as something to treasure, and made his second trip to Abiquiu this summer. Grinding (and grinding, and grinding) for exquisite results: Part of my wandering took me to an outdoor space where participants were busy creating natural pigments under the direction of Chris Riederer, an expert in gathering, grinding, and powdering substances that will eventually morph into paint. When I met him, he was busy grinding yellow and red ochre he had discovered on the front range of Colorado’s Fountain Formation. Chris’s rocks were between 60-70 million years old, their dates determined by nearby dinosaur remains. Two participants were using a glass muller to do the final detailed grinding of malachite, a stone worn in Europe as late as the 18th century to ward off demons. The program’s purple pigment was extracted from stones discovered on the Dar al Islam property. Seeking the Divine Through Beauty: Once he’d finished guiding students on grinding pigments, Chris Riederer taught more classes, including one on biomorphic patterns, an artform that uses images from the natural world, such as plants, vines, often intertwined with Qur’anic verses. This artistic style is so prevalent in Islamic art that it’s often referred to as Arabesque art, or art in the Arab style. It’s found in paintings, sculpture, woodwork, even architecture. Perhaps the most famous Arabesque work in the world it the interweaving of sacred verses with vine patterns found at the Alhambra Palace in Granada, Spain. If you look closely at the striations in the leaves, you’ll see they’re not striations at all. They’re Arabic letters, spelling the word Allah. In the Islamic tradition, everything God created can serve as a reminder of His presence. Muslims are encouraged to contemplate beauty as a path toward remembering God while also noting the need to focus on our interior nature as well. For this reason, there is no division between artistic expression and the person surrounded by artistic beauty that expresses a transcendence and order that rises above the chaotic world in which we live. Faculty member, Samira Mian, came to Abiquiu from London to teach a class on Geometric Patterns. When I arrived at the site and asked someone where I can find her, their advice was to look for the woman whose face shines like the moon. That’s all I got. I spotted her immediately. Samira guided her students in making repeat patterns based upon an underlying geometric grid that they drew. Soon her students were creating complex works under her guidance. To further demonstrate the underlying geometric patterns behind Islamic art Adam Williamson, program director, walked participants through a step-by-step process that took them from this: (Pay attention to the location of the horizontal line and the two circles.) The link between geometry and Islamic art was further expanded by New Mexico’s own Jay Bonner. After graduating from the Royal College of Art in London, Jay became an internationally recognized specialist in design methodologies employed by traditional Muslim artists including design techniques, and the methodology employed in the creation of particularly complex geometric patterns. Muslims making the Hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah) can see Jay’s work at both the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina and the Grand Mosque of Makkah. His book, Islamic Geometric Patterns: Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction, is used worldwide by scholars of geometry, history of mathematics, history of Islamic art and architecture. Besides teaching classes for the program at Dar al Islam, Jay was very generous in sharing his knowledge and support to students such as Rebin Muhammad and Alexandra Veremeychik, co-founders of MathArtPlay, a creative collaboration at the intersection of mathematics, art, and education. Their team brings together mathematicians, artists, and technologists who believe learning should be hands-on, beautiful, and meaningful. The perfect combination for teaching math and Islamic patterns at the same time. They design curriculum and perform outreach to students from the elementary to high school level. (You can learn more about them at mathartplay.org) Another attendee who plans to teach what she learned here is Paula Bickham of Charleston, West Virginia. She has already arranged to share her skills and knowledge in workshops at a community center that serves the elderly population of her city. Just how hard can this be? The purpose of geometric patterns within sacred art of any faith system was beautifully set forth by the prominent 11th century Muslim scholar and philosopher, Imam al-Ghazali who wrote: “The function of geometry in art is to remind the soul of the divine order behind the veil of material existence.” Lessons continued on sacred geometry under the guidance of Lisa Delong who told me her particular love is Geometric Pattern. Her art journey was set in motion by a professor at Brigham Young University who taught that art should be based on proportion and harmony. His teachings led her to travel to London’s School of Traditional Arts where she met several of the other faculty at this Abiquiu workshop. Based in Utah, she now coordinates public community workshops at several international teaching centers for the School of Traditional Arts including programs in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, China, and at a soon-to-open program in Uzbekistan. In her classes and her writing, Lisa stresses the importance of the circle (symbol of the heavens) as well as the square (symbol of the earth). This translates into Islamic architecture through the practice of placing a round dome on top of a square room. How does one do that? By using something called a pendentive (symbol of the angelic realm that sits between heaven and earth.) This curved triangle, called a Muqarna in Arabic, can be simple, such as the ones at the Dar al Islam mosque, or they can be elaborate, even “honeycombed” like many in the Middle East. As the program wrapped, participants packed up their projects, compasses, paints and ceramic tiles made under the tutorage of faculty member Fabiola De la Cueva, before saying goodbye, and promising to gather again in the Land of Enchantment. Interested in seeing the geometry behind France’s famed Rose Window of Chartres Cathedral? Here’s a link to a fascinating animation by Michael Schneider on how that design developed: https://www.constructingtheuniverse.com/chartres%20animation.html

|

Submit your ideas for local feature articles

Profiles Gardening Recipes Observations Birding Essays Hiking AuthorsYou! Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed